Planet Drum appreciates the many volunteer hours Karie Crisp spent contacting contributors, editing their writings and organizing them for this page.

Welcome & Introduction:

Dedicated to Peter Berg

Congratulations to Planet Drum Foundation on 50 years of bioregional advocacy and education!

Planet Drum Foundation continues to inspire individuals and communities. When I consider those beating the drum of change for 50+ years, my own resolve strengthens and I want others to know this history that continues to ignite hearts and minds.

Not long after I began volunteering for Planet Drum, I started thinking about ways to celebrate the non-profit’s golden anniversary. One of my ideas was to collect stories, remembrances, and statements from people engaged in this five-decades exploration.

Here they are—the voices of thinkers, activists, artists, and everyday individuals whose lives were touched by Planet Drum. Each contribution offers a unique perspective including personal experiences, essays, poems, and calls to action.

This collection not only honors the legacy of Planet Drum Foundation, but also serves as a call to future generations to protect our planet’s ecosystems and nurture a planetary consciousness that values ecological sustainability and place-based culture. I express my heartfelt gratitude to all those who contributed and to the countless individuals around the world who put their lives on the line every day to resist what Peter Berg called “Earth-colonist globalism.” May these stories serve as a wellspring of inspiration for future generations.

All in. Let’s go!

—Karie Crisp, June 29, 2023

- I want to send a special thank you to Juan-Tomas Rehbock who meticulously kept bioregional archives and suddenly passed away before he was able to contribute to this collection. May he rest in peace.

Karie is a graduate student in integral ecology and political philosophy; she lives in unceded Ramaytush Ohlone territory near Northern California’s largest estuary.

<<<<—————–>>>>

This page welcomes additional stories, remembrances, tributes, cranky comments, etc. about encounters with Planet Drum Foundation. Send them to Planet Drum Foundation at mail@planetdrum.org

<<<<—————–>>>>

Entries are posted as they were received. Use the links below to jump to a particular person’s entry.

Planet Drum Stories, Remembrances, and Regrets @ 50

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Jean Lindgren – November 17, 2021

I owe Judy, Peter and Planet Drum a lot….you all changed me from being a very angry pissed off person into one dedicated to benefitting the Earth however I can. I’ve learned more and more each year I’ve been working for Planet Drum and that’s an ongoing process.

Jean Lindgren has worked at Planet Drum since 2002 and lives in the Shasta Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Art Goodtimes – January 18, 2022

-for Peter Berg & Judy Goldhaft. Update of a previously written poem:

Reinhabitation

I spent the first night alone

in the abandoned house

dropping acid

to see what I could see

outside myself

And I’ve spent the past

forty years inside

this acre of irrigated wetlands

learning itki’s quandaries

How poplars gnawed down

to the roots by deer

grow stronger

Survive the drought

that kills the cherrytree

How native lacewings

encouraged in their spidery nests

love to feed on Canada thistle

And how some weeds harvested

before flowering & soaked

in drums of pond water make

the stinkiest best compost tea

Each spring. Each fall

Wind before the clouds

whipping at the roofs

tossing gusts & ghastly turns

A neighbor crushed in her truck cab

by a snapped cottonwood on the highway

I’ve even learned

the litany of locals who called

this place home

Mex Snyder. Caroline Young

Ed & Grandma Foster

Planting rhubarb. Tending goats

And now paid for twice

Cloud Acre’s been mine to husband

Siberian elms. Coyote willow

Forty-nine varieties of

heirloom spuds grown to seed

Two once-small children

Two grown & long gone children

Flocks of geese. Red-winged blackbirds

The occasional Great Blue Heron

Listening to this one place

Itki’s names, itki’s moods, itki’s whispers

Listening has taught me more

about earth kinning

& the land’s deepening wisdoms

than any text

art goodtimes

union of mountain poets

vincent st. john local / colorado plateau / aztlán

cloud acre brigade (ret.) / san francisco

13022

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Giuseppe Moretti – July 1, 2022

50 Years of Planet Drum

After AAM (Agriculture, Alimentation, Medicine) Terra Nuova, a monthly journal of the alternative, gave up on pursuing the bioregional idea in Italy, I found myself alone insisting on this prospect of change. Nobody knew me at that time (late eighties), also because working on my father’s small farm absorbed all my free time. If we add to this my innate shyness, which meant that even in those few AAM bioregional camps in which I participated, my voice was hardly heard. Notwithstanding of that, my conviction of the validity of the bioregional proposal was such that I really didn’t want to see it abandoned. And that was how the publication of Lato Selvatico began. A modest newsletter, written partly by hand and partly with a simple old typewriter (it was 1992) and sent for free to a few targeted addresses. That was literally a “stone thrown into the pond.”

I encountered Peter Berg and Judy Goldhaft the year before at the first meeting for the Shasta Bioregional Gathering in California. Two years later, in 1994, I received a letter from Peter in which he informed me that he and Judy were about to leave for Germany and that I could take this opportunity to organize some meetings on bioregionalism in Italy. I contacted the few whose attention Lato Selvatico had captured and together we organized six conferences up and down Italy: Mantua (Green University), Bologna (Frontiere), Ravenna (Appropriate Technologies), Rome (La Sapienza University), Naples (Flaming Rainbow) and Florence (AMM Terra Nuova). Peter’s eloquence on the bioregional theme and Judy’s art, with her performance “Water Web,” broadened the minds of the audience to discover that the world is not just one of power games, economic interests, or the megalomaniac dream of modern society which continuously absorbs energy and makes us feel powerless. Rather, the immediate world in which we live, the bioregions, provide the place to build the foundations for another world based on respect for ecological processes and social aspects of a just and aware society.

The bioregional arguments as expressed by Peter and Judy were so new, visionary and explosive that there was no shortage of criticism in the newspapers, especially from the environmentalist green area. But for me and for the other aspiring bioregionalists, Peter and Judy’s words gave shape and vigor to a movement that at that time was in its infancy. The movement later grew producing coordination at the national level (Rete Bioregionale, 1996/2010, and Sentiero Bioregionale, 2010 to now), local and national annual gatherings, presentations and conferences, plus the publication of books and newsletters (in addition to the aforementioned Lato Selvatico).

The collaboration with Peter and Judy never failed so that in the following years they came back to Italy for conferences in Universities and Social Centers. They also came as Guard Fox Watch in 2003 to monitor the Turin 2006 Winter Olympic Games. I enjoyed their hospitality in the headquarters of Planet Drum on several occasions. We all miss Peter, a real warrior for Earth!

Giuseppe Moretti is an organic farmer, is part of the Sentiero Bioregionale group (www.sentierobioregionale.org) and is editor of the Lato Selvatico newsletter. He lives in the Po River Watershed Bioregion in Italy.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg – August 5, 2022

Meeting Peter, Judy, and the Bioregional Movement

We were holding hands in a circle, 200 or so of us, singing Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” somewhere in the heart of the Ozarks in 1982. It was the second Ozark Area Community Congress (OACC), and I was lured there by hearing David Haenke, one of the congress organizers, six months earlier sing another song, Joni Mitchell’s “Same Situation,” outside of Ernie’s Cafe in Columbia, Missouri. It wasn’t a well-known song, but a very well-loved one by me, so I followed the music.

Now the multitudes of us who followed music or lust, yearning for adventure or an earnest wish to live lives that matter, were here together, holding hands and swaying. I looked across the circle and saw Peter and Judy, moving with elegance and panache. I looked up and saw the tent swaying, and beyond it, the clouds easing across dusk just before the swaying stars would make their presence known.

In time, I was hugging Judy and looking deeply into her beautiful eyes. I was holding Peter’s hand. I was in love with everything and everyone, at least for a while, but let me be honest: I was also, for the first time in my life, on acid. Most others around me probably were too.

A few hours before, when we were introducing ourselves around the massive circle by stating our name, home, and why we were there, a middle-aged man with long brown hair and a mustache too big for his face said, “I’m Rank N. File, I’m from the CIA, and you all know why I’m here.” Within short order many realized he was telling the truth because after introductions he passed out hundreds of tiny Mickey Mouse squares of paper, LSD, for everyone to try. My heart was so open by the oaks, the pines and the kindred humans looking into my eyes to acknowledge that we were old friends that I followed along.

So, the tent swayed. The clouds swayed too, and in time, I saw hands re-arranging them. Mostly though I was encased in a horror of flashing lights and torn rusting metal, realizing too late that the drugs were an irrevocable mistake, and I was trapped in six or so hours of horror-tripping when I meant to be loving up trees. Did Peter and Judy drop acid too? Maybe because whenever I ran into them that night, we clutched each other and laughed hysterically. Peter’s laugh could leap tall walls, then lie down in the grass and astound the sky, and Judy also had a lovely way of dancing in half circles to each side while laughing.

The drugs were a mistake for many of us, and surely, they were meant to derail what we were really there to do and be, making us into tripping hippies rather than a body of people talking, planning, and singing their way toward a more perfect union with this living earth. Waking the next morning, I felt like a train had thrown me hard into the hard earth, everything sore and my mind blinded by a migraine. I was exhausted and wrung out, but eventually I would find my feet and breathe again in love with this movement, these people, this earth.

But how that first gathering grabbed hold of me. It blasted and sung open the world as I always knew it without yet knowing this was my truth, and I had good company. Sometimes one thing—like an obscure Joni Mitchell song—or deciding to walk down this block instead of that one changes your whole life. Following the music to bioregionalism was that for me, first to OACC and six months later to the Kansas Area Watershed’s (KAW) first gathering in 1983. There, I would meet my husband and many of my closest friends, not the least of which was the community and eco-community of Lawrence, Kansas where I would plant myself for life.

***

I saw Peter and Judy again in 1984 at the first continental bioregional gathering, then called the North America Bioregional Congress (NABC). At the camp near Kansas City, Missouri, we shared some meals, surely laughed our way into the spine of stories Peter, a story-spinner of great renown, told. We were clear-headed but perhaps because of the gonzo swirl and sway of our initial meeting, I felt like we were old friends.

I met Stephanie Mills who dazzled me with her articulate passion for interior and exterior wildness. I watched the Paul Winter Consort floating in a series of canoes on the lake as they performed. I sat in a lot of meetings, including the first plenaries where I saw the facilitation genius of Caroline Estes and glimpsed how people could truly find collective wisdom and common ground, especially across grand divides and old wounds. The men at the congress took turns sewing the new bioregional quilt together, each square made largely by women throughout the continent.

As part of the planning committee with other OACC and KAW people, I also worked my tail off rushing around to haul groceries or help in the kitchen. An old handout of meeting notes I recently found tells me I was transportation coordinator for the event although I can barely remember what I did in an age long before emails and the interwebs.

But throughout the congress, there was something about Peter, there was something about Judy, and there was everything about Planet Drum’s dream that permeated and shaped all we did. Peter’s “Amble Towards Continent Congress,” a manifesto written in 1976, was the blueprint beneath the house of the congress we built in the wild.

Those nights, sitting around campfires or walking quietly along the woods from the lodge to the cabin, were filled with an open promise of what was possible. There weren’t any hallucinations of hands moving clouds but instead the refreshing reality of us all there together, talking and listening to what might come next. Mostly, I listened to the wind and to my own heart settling into a deeper sense of home. Many of us were doing the same.

***

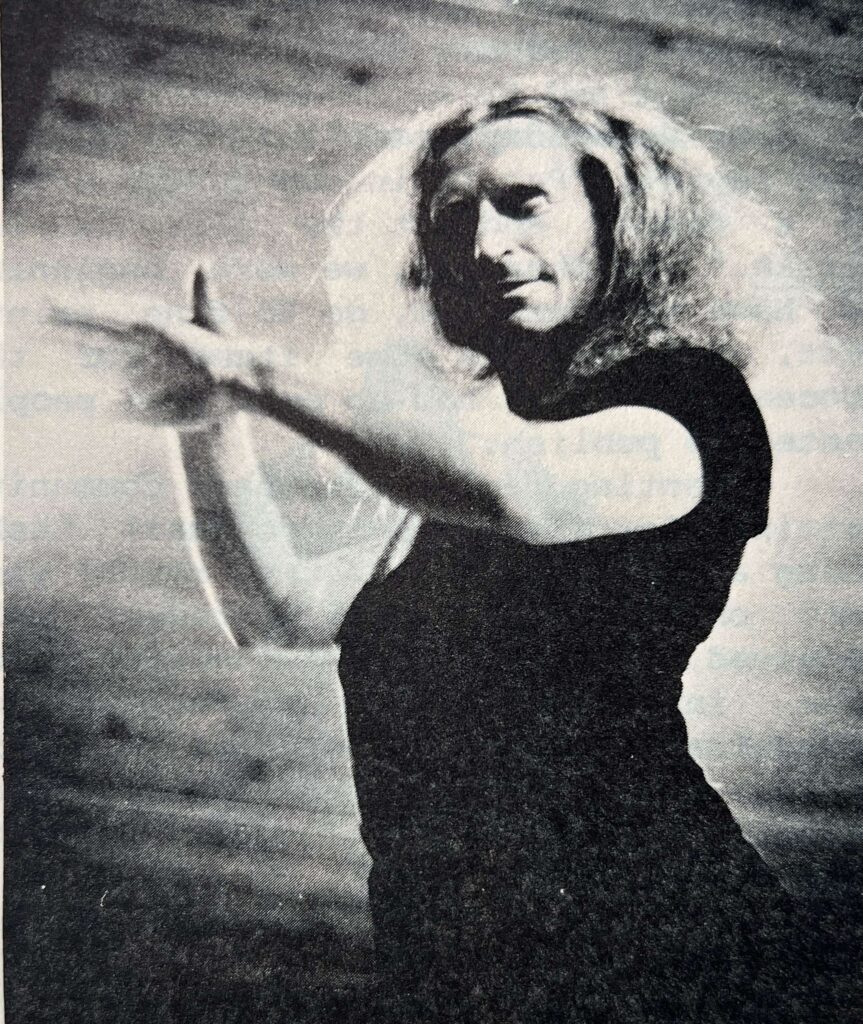

She lifted both her arms, her loose blue kimono rippling around her like water as she swirled and spiraled down on the stage. I swayed side to side with my newborn daughter, just two weeks old, pressed against my chest, both of us sweating. We were near San Antonio, Texas, mid-May, 1992 for another bioregional congress. I had caravanned down with other KAWsters, most notably Ken and my family, including our new being. Just past dusk, most of us at the gathering stood and sat in the cooling air watching Judy do the water dance, something she developed in a more ancient dimension and returned to us at each bioregional gathering.

This time I watched her with new eyes, exhausted and also in love as I felt Natalie root around my chest for more milk. I hadn’t slept much in the bunk beds of a far-off dorm where the congress organizers thankfully put our family. We hadn’t recovered from the twelve-plus-hour drive with a toddler and a newborn, both Ken and I birth-weary but determined to be at the gathering. The kids did fine, sleeping a good amount, but we were another story, trying to relax on the road and now at the camp in between so much ecstasy and exhaustion.

Just as I looked for a place to sit, a young man brought me a plastic chair and asked if there was anything else I needed. No, just this. Just sitting here, nursing my newborn daughter while watching Judy lift and spin, still and rise, pause and arch her back to take in the sky, starting to churn the humidity of the day into the rains of the night.

We’re all made of water, she reminded us in a language beyond words. Yes, we are, my body, my daughter’s body, sang back to me in the quiet of the still air right before the wind of the storm makes its way through the crowd and the open space around us.

I knew Judy and Peter’s daughter was named Ocean, whom I met both when she was a child and a woman. I knew Planet Drum hugged the edge of the land on the west side of this continent. I knew all was fluid and in motion, but Judy was showing me something else at that moment as she enacted water and a woman moving through water. She gave me a wider glimpse of the life ahead, the moments now so precious and seemingly contained of this deep-dish motherhood, the moments behind and the moments ahead, all rolling through our bodies and lives like weather.

***

Sometime in the late 1990s, I was in San Francisco for a drama therapy conference, there because of my work founding and growing Transformation Language Arts, an MA program I started at Goddard College, and an emerging field all about using writing, storytelling, theater, and more for community-building, healing, and social change. But San Francisco was, as always, crazy-expensive when it came to hotel rooms, so I stayed with Peter and Judy. The conference also turned out, for me at least, to be a bust: over 350 people doing wonderful work in drama therapy and psychodrama (yes, an actual field of using theater for healing) together don’t always make for a very welcoming conference to outsiders. So, I punted and walked the city in between talking with Peter and Judy.

“You’re moving differently. Something has changed in you,” Peter told me one morning at their kitchen table over breakfast.

“He sees these things,” Judy added.

He was right. I had just weaned my third child after eight years continuously pregnant or nursing, and I was returning to my body as the habitat mostly of one human. He looked right into my eyes from across Judy and his kitchen table. “Yes, something has definitely changed.”

I drank the last of my honey-sweetened coffee and smiled, so content to be seen as someone who had arrived on the other side of a passage and someone ready even for whatever came next although of course I couldn’t know what it was.

There’s something about bioregionalists who have hooked into the power and presence of the ceremonial village we create together that basically downloads what bioregionalism is into our bodies and psyches. It also makes kin of strangers, so much so that many of us feel like we could walk into each other’s apartments or houses, open the fridge and root around for some good leftovers, read each other’s magazines, and nap on one another’s couches. This was what it felt like to be at Judy and Peter’s place, an apartment connected to the Planet Drum office, city and Max Parrish-like city skies integrated and of one piece.

I promised myself I would visit again, feeling so at home in their presence, but 1,500 miles between my home and theirs, the tears and pulls of time, and all the workaday ramblings that overflow a life kept me from keeping that promise. Yet I have that visit, that conversation, that breakfast to remember.

***

Where does time go and how does it move? This grabs hold of my poetry and yearning to know something more solid in a world of constantly shifting weather and water, movements and gatherings, meetings and departures.

Peter died too soon and yet over eleven years ago, a mere 73 years in age although much older in bioregional time given his still-unfolding legacy. He was the original raconteur, a performer of space and place, a visionary and curmudgeon. He was fearless and loving, present and a bit omnipotent, even when alive. He and Judy started the Planet Drum Foundation decades before we knew what was coming but surely on the basis of what was on its way.

I remember at the first bioregional congress in 1984 how people were debating whether there would be a new ice age in our lifetimes or global warming. Obviously, the latter won out. But the movement, which he named into existence, all of us who came to it further unfurling its language and possibilities, was way ahead of the game, even if we were and still are bent on dismantling the game and making something better. Especially if we realize there is no real game at all, but the something better is simply what is here: the earth in its most local forms, including our own bodies and where our bodies dwell, in real and specific time.

I remember reading in the L.A. Times after his death how he once tore up the sidewalk outside his and Judy’s home and office with the intention that seeds from what they planted would “blow down the street and crack open all the sidewalk with native plants.” That’s what he left us: seeds capable of cracking open sidewalks and lives.

That’s what Judy and other Planet Drum people carry forth while Judy especially shows us, the Jill-of-all-trades she is, in her sinewy ways of moving. She keeps dancing it together and beyond those walls out to where there are no walls.

When I think of Judy and Peter, I still think of them swaying arm-in-arm with all the others under the swaying tent and sky while we all sang “Suzanne.” I think of the rain blessedly coming. I think of the clearing afterwards.

Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg is a long-time bioregionalist and one of the founders of the Kansas Area Watershed Council. Past poet laureate of Kansas, she is the author of more than 20 books of poetry, fiction, memoir, and anthologies, and founder of Transformative Language Arts. She offers classes, workshops, writings, and coaching on writing for our lives, Right Livelihood, and facilitation. She and her husband, ecological writer Ken Lassman, make their home and are made by it on the prairies of Kansas, just south of Lawrence, Kansas. For close to 40 years, they’ve worked, prayed, struggled, freaked out, schemed, dreamed, and planned to save the land where they live, and in 2020, they were able to buy that land, which will be placed in a conservation easement to protect it forever through the Kansas Land Trust.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By John Diamante – November 22, 2022

I was influenced by the early mapping work of Erwin Raisz. His landform cartography was drawn in pen and ink. Apart from my childhood’s pictorial poster maps of the world’s peoples, their habitats and various species, from murals by Miguel Covarrubias for the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair, it was the first time I saw a map without the normally basic anthropocentric information such as cities, political boundaries and other clutter.

For me, it’s always been the watershed as the basic political unit, though there is a certain inter- changeability between watershed and bioregion. The word “bioregion” has gone from an arcane term (still not quite a kitchen word) to one at which most people don’t react blankly. As wellsprings of the bioregional movement, one would have to identify Planet Drum Foundation and, among early articulators, latterly David Haenke and the Ozark Area Community Congresses (OACCs).

Planet Drum’s legacy to date is a multi-media (largely print and theater) dissemination of hearts-to-Nature call to how we might live, specifically, in Planet Drum’s terms, how to reinhabit place. The word “reinhabitation” kind of says it all—how to adapt our human needs and lifestyles to eco-systems of different (wilderness, forest, preserve, rewilded, regenerating, prairie, farmed, ranched, ecotone, montane, alpine, desert, riparian, oceanic, island, coastal, urbanized, megapolitan] bioregions, watersheds and deltas, successfully to live with, not against or degrading the natural world.

A watershed can be very small, a microsite such as the headwaters or tributary stream of a river. On the other hand, the National Recovery Administration (of “dirt farmer,” arborist FDR’s New Deal) administratively organized programs addressing ecological distress and economic depression of the 1930s according to macro watersheds (Columbia River, Colorado R., Tennessee Valley Authority, et al.; i.e., today, federal regions could be referenced as identified regions instead of Roman-numbered Districts: I, II, III…)! There are different scales but it seems plain that people attuned to place are going to have to look to their ingenuity and proficiency, intimacy with Nature and handiwork with tools (oriented from Stewart Brand and crews’ Whole Earth Catalog on) to survive payback for a century’s depletion of resources and driving, we thought, oh, so freely, swiftly, luxuriously, privately—in polluting, carbon-based, pavement’s traffic-trapped (auto)mobility.

I became acquainted with the Peters (Berg, Coyote, Warshall), Judy Goldhaft and crowd through a group called Reinhabitory Theater. Based on indigenes’ tales, they performed engaging plays in San Francisco parks, cavorting semi-costumed, mostly with masks. I got to know the continental movement of place-based thinkers and doers better through OACC, participation in several of the NABCs (North American [Turtle Island] Bioregional Congresses, 1980s to ’90s) and a Shasta Bioregion gathering held in North Coastal California.

Congresses were hosted by allied inhabitants of proudly identifying bioregional areas including the Ozarks (1984), the Great Lakes (1986), Cascadia (British Columbia, 1988), the Gulf of Maine (1990), Edwards Plateau (Texas, 1992), Ohio River Valley (Kentucky, 1994), Cuauhnahuac (Mexico, 1996), the Prairie (Kansas/Kansas Area Watershed/KAW, 2002), Katúah (Southern Appalachia, 2005), and the Cumberland bioregion (Middle Tennessee, 2009). They were like very grounded and joyful summer camps with a couple hundred (mostly white, except in Mexico) people, including families and lots of children, with intensive showing, trading, recreations, entertainment, Turtle Island and Mother Earth circles, dancing, late-night earnest deliberations and jawing.

We San Francisco watershed evangelists also nourished each other at The Farm (a wood building underneath the intersection maze of Cesar Chavez Blvd. [Army St.] and 101 freeway). This cross-roads meeting place of many arts was created by recently deceased reinhabitress (New York City’s Bryant Park to San Francisco’s Mission Creek), Bonnie Sherk, assisted by Jack Wickert and Andy Pollack (who has founded a multi-activity “SF New Farm,” with various species and artists, integrating both a native plant-dedicated and additional nursery, at 10 Cargo Way’s Bay shore).

I remember the concurrent All Species movement (including us two-leggeds, not the other way around) with Chris Wells, launching year-long schoolroom work-ups of costumes inspired by self-chosen animal and vegetable totems, that climaxed with spectacularly inspiring All Species Parades on officially proclaimed All Species Days, from San Francisco to Manhattan among other metro centers.

The San Francisco Ecology Center, at 13 Columbus Avenue, one of Zach Stewart’s inspirations, directed by Gil Bailie, then, Marc Kasky, (at once a venue for all sorts of meetings and presentations, a gallery, and thronged, Financial District, lunch-hour Soup Kitchen) was frequented by downtown workers, tourists, water and resource stewardship pioneers, authors, photographers, artists, incantational summoner, Ponderosa Pine, and other, full-blown, eco-invocatory, bioregionalist enactors.

One can’t say enough about the dedication, inspiration, originality and integrity of Planet Drum’s work and mission to seed and spread bioregional understanding—Nature first and adaptation promoting a future for Earth’s interwoven ecosystems and species, in harmony with one’s chosen region. I was happy as an independent, friends-financed NGO (nongovernmental observer) and proudly as a San Franciscan, to carry a “bioregional portfolio” of Planet Drum’s and related maps, texts and graphics to various U.N. and multilateral conferences and plenipotentiary reviews (such as the protracted Law of the Sea negotiations), in the ’70s and ’80s.

Planet Drum’s “bundle” concept was a key contribution to the bioregional movement as a medium of assembled representative media. Each unique whole bundle was brilliant, indeed awesome, motivating inhabitants of very different regions to signify, to express their place, in poetry, prose, art, texture, memory, everything but (only for lack of budget) audio and visual media. They were so inventive and marvelous. Everyone who received even one bundle, especially the series, was converted. Perhaps the work of them should be repurposed in comic/graphic book form to reach new hands (bundles were max tactile), eyes, senses and minds.

Planet Drum is a small press, an esoteric thing in the landscape of publishing, and small presses struggle. The influence and impact of its output deserves funding appropriate for republication and new originations. Planet Drum’s fantastic work has progressed on a Mickey Mouse scale compared to what the content merits. What’s the mailing list membership base—a few hundred maybe? But poets are the true legislators, artists and teachers of humankind, right? Planet Drum Foundation has been a poetic source of orientations and truth.

The opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympics are the largest of media and theater productions. What if ecological commitment had been favored, endowed to work at that scale, symbolized by benchmarks from Earth Day to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth? Planet Drummers could mount Come-to-Nature revival shows with a big tent, music, projections, and voices of all species, drawing people in using song, culture, lore, insight and humor of a venue’s region to lift up and unify. Immersive revival theater could be done with bioregional content, for instance: this is where we live, this is what we’ve done, what we are doing to the place, plus flourishing upsides if we can change. Bring people to that same emotional pitch of openness to each other as at the great rock fests of the ’60s and beyond—such as Grateful Dead concerts where several thousand people danced in harmonic, euphoric wisdom. Take the tent(s) on the road, camp in reaches and precincts and celebrate life oriented to Nature. Facilitate connections to life using sung and spoken word, music, dance, image, news, data. Attract people to amassed experience, dissolving frames, connecting capabilities of individuals, families, affinities, consumers and voters to live nourished by and nourishing Nature. How to amplify beats of tolerance, peace and cooperation? Scale tent-sized or arena-full, enveloping, green-content theater for 5,000 or 50,000 people at a time.

A few memories…

I remember Judy always working and laughing, celebrating. And providing—real makers of movements are always to be found in the kitchen as well in colloquies, ateliers, onstage and, when the chips are down, on the front lines. Peter was a very gifted and gutsy person, like all leaders, creatives and authentic disruptors. He was a born director and could be a tough taskmaster with a barbed, acerbic side. I decided early on I wasn’t going to let that bother me. He was a wonderful and magical person.

Together, the two of them were a magical pair. We’re in debt to Judy, staff and volunteers for carrying on the catalytic, prolific, high-spirited, humor-loving, faithful reporting of Green City, Pulse and related Planet Drum chronicles.

Another memory of spending time with Peter and Judy is the hospitality of their house and the paper (pre-digital) information produced by that house. We’re all aging. Who’s going to take on the archives, hard copy (for permanence) and digitized (for global access)? What institution or library will serve as the repository? Big question—how can all of us help Judy and staff, fiscally, logistically with where the working, openly accessible output, as well as unique holdings of Planet Drum might be situated? The move will free up Judy’s life and free us, in knowledge that PDF will long be drumming.

map!

And, to the matter at hand: celebrating 50 years of Planet Drum. Since NABC and to this day, I don’t think I’m alone in wishing for continental distribution of a colorful, pictorial, diner-, truck stop-, café-, classroom-, student union- and government center-popular, simple, QR code-graced, Planet Drum 50th Anniversary (North American for starters) map of bioregions.

coders!!

What about the game? Of life! In the massive, multiplayer, dominant entertainment industry of online gaming’s immense demographics, find, inspire or follow talented coders, to transcend the genre’s primary, first-person-shooter product with an individual and team game of high-humored, first-person(s)-reinhabitor, bioregional challenge—for an epiphanic gift to the commons. All rights and revenue (overseas, copyrights, any media, merch spectrum), however, securely to be held by and accrue to Planet Drum Foundation, Inc.

John Diamante is an independent creative whose half-century of Special Projects (Public Communications, Inc., and Threshold (Center for Environmental Renewal, Inc.—Way of Nature) has included research, writing, networking, tactical newspaper publishing, advocacy planning and direct organizing for long-cycle public benefit causes and coalitions. His proofreader.com shop provides full editorial services. From the Bay Area, Shasta Bioregion, he regularly travels coast-to-coast by rail. For (print or digital) Special Projects’ 14th Draft of a ‘sheet-to-beat,’ single-page roster of 22 infra[eco]structure priorities, fronting May ’23 Edition of 11″x17″, full-color, USA railway network urgency, map folder: contact by voice @ 202.203 9100 or write @ 268 Bush St., 1009 SF CA 94104.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Daniel Christian Wahl – March 31, 2023

Our ancestors around the world for nearly 290 thousand years of the Homo sapiens story have been custodians of the bioregions they emerged from, dwelled in, and were expressions of. The return to becoming a cosmopolitan bioregional species through what Peter Berg called “reinhabitation” is our collective path towards planetary healing and a regenerative future. The work of Peter Berg, Raymond Dasmann and the Planet Drum Foundation was 50 years ahead of its time and has never been more significant than today.

Daniel Christian Wahl is an educator, activist, agroforester and author of Designing Regenerative Cultures. He lives in Mallorca in the Balearic Archipelago in the Western Mediterranean.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Peter Brastow – March 31, 2023

My relationship to Planet Drum (PD) goes back to the mid-1990s when I was interning for the National Park Service at the Presidio. I applied for a job at PD in 1996 and had an interview with Peter Berg. Though I didn’t get the job, Peter said that our paths would cross in the future, which of course they did at various times. One of those was when Peter and the Mayor of Bahía de Caráquez, Ecuador (where PD had a community restoration project since the 1998 El Niño), served on a panel that I organized for World Environment Day, 2005, which was held in San Francisco. Later, Chris Carlsson and I collaborated on the Shaping SF/Nature in the City TALKS at Counterpulse, and Peter and I were on a panel together with Bonnie Sherk talking about strategies to create a Green City.

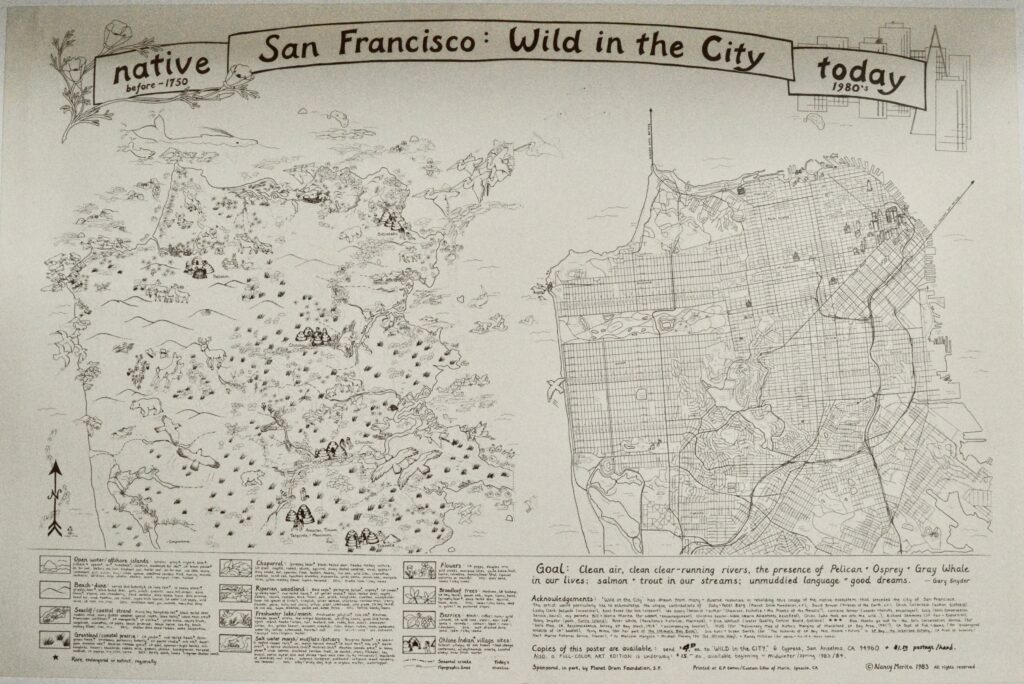

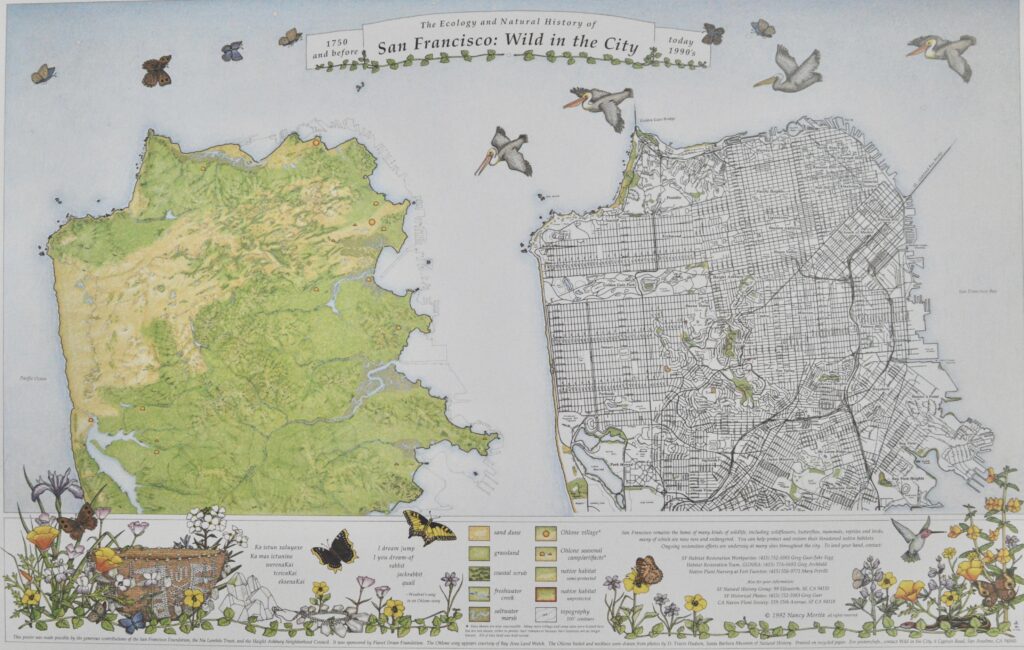

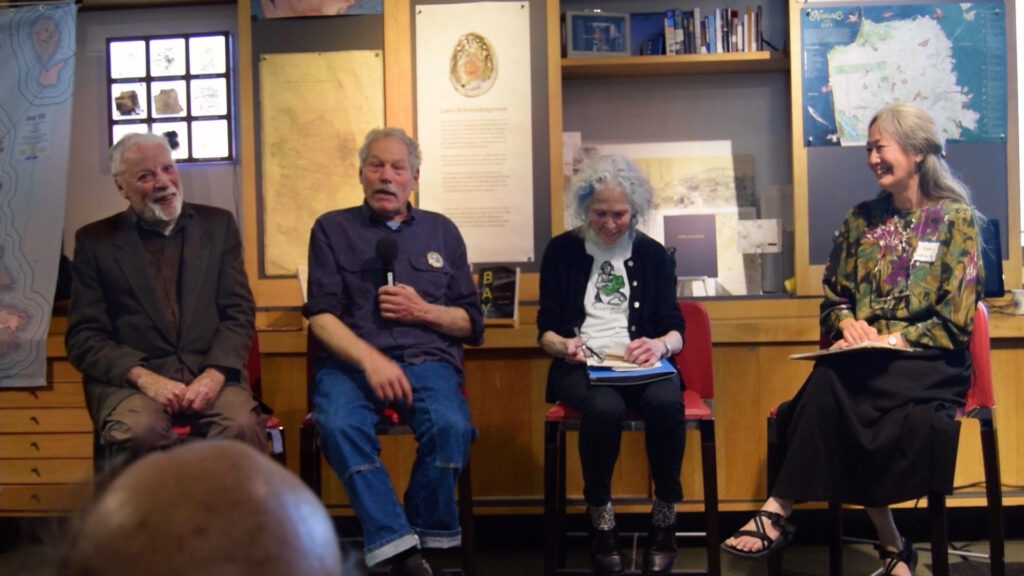

My deepest connection to Planet Drum, Peter, and Judy is of course the concept and vision of bioregionalism. After encountering this and other ideas while I was studying geography at UCLA, I immediately began putting them into practice when I started to volunteer doing habitat restoration at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. I loved how PD would always include the Shasta Bioregion on their address, and for the last 30+ years, we in the local nature conservation movement have always framed our work as part of restoring the Franciscan Bioregion, which was first coined by the botanist James Roof. Finally, in 2006, I started to promulgate the idea of creating a Twin Peaks Bioregional Park, which is still a very viable idea and directly complements the grassroots-created Crosstown Trail. Speaking of 30+, the most obvious manifestation and inspiration of Planet Drum’s bioregionalism is the Wild in the City map, which PD sponsored back in 1992. We honored the map’s contribution, including that of its creator Nancy Morita, recently at a wonderful event at the Bay Observatory at the Exploratorium (March 2023), where we also showcased examples of all of the astounding ways that people have been inspired by the Wild in the City map’s bioregional vision for all these years. And bioregionalism is absolutely infused into San Francisco’s 2018 Biodiversity Resolution and our bold chapter for Healthy Ecosystems in the City’s 2021 Climate Action Plan.

Peter Brastow is a Senior Biodiversity Specialist and Yerba Buena Island Restoration Ecologist with the San Francisco Environment Department in the Franciscan Bioregion. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Robert L. Thayer, Jr. – March 31, 2023

Congratulations to Planet Drum for its 50th birthday (this year is also my 50th as a professor at UC Davis, now retired). I attended the Shasta Bioregional Gathering (SBG) III on the Big River camp in Mendocino in 1994 and SBG IV at Cazedero in 1995.

The two SBG gatherings I attended were very important and pivotal events for me. Four other professors and I had put together a Putah-Cache Bioregion Project at UC Davis in 1993, and for me, attending the SBGs was essential. I remember vividly when Peter Berg had us form a spatial “map” of where we came from on the dining room floor, each person standing in their own small place with regards to Northern California. I was also quite moved by Judy’s history of Planet Drum, and by Malcolm Margolin’s fascinating talk about native California groups and their relation to the land and to each other.

Prior to attendance, we were all asked to bring a container of water from our home stream; I pick up mine from Putah Creek on the way to the Russian River, and in ceremony, each poured our water into Austin Creek. I was quite moved by this simple gesture, and later instituted a similar water-sharing ritual on Utah Creek by a diversion dam: each person gathered a container of water from above the diversion dam, later to pour half of the water in the diversion canal for people and the other half into the stream beyond for fish and other creek animals.

These two bioregional gatherings were essential life changers for me, as if I had been baptized as a bioregionalist, which I remain today. Planet Drum IS the birthplace of the bioregional movement. More recently, I have reminded many of my bioregional colleagues around the world of this critical role Planet Drum played, and the rest of us are loyal followers spreading the word.

Robert L. Thayer, Jr. is Professor Emeritus of Landscape Architecture at the University of California, Davis and is remotely working on another Ph.D. at Kingston University in London. He resides in the Putah-Cache watershed subregion of the Sacramento Valley Bioregion of Northern California.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Stephanie Mills – April 3, 2023

Planet Drum 50th Anniversary Encomium

Trying to come up with an adequate tribute to Planet Drum on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary has taken me through some of my own archive of bioregionalia, thence to the internet and home to my own love and respect for Peter, Judy, and Freeman, treasured friends, remarkable people with wonderful minds, all kinds of courage, brilliant imagination and utter commitment to Nature’s primacy on Planet Earth, with unyielding hope for human species kind to reinhabit the biosphere one life place at a time. Along with companeros they began Planet Drum, a crucial node and polyphonic voice of bioregional thought and action.

Early on, Planet Drum’s savants understood how cruel and serious things were getting and that more of the same old piecemeal tweaks and reforms wouldn’t help for long or inspire for the long haul. So they dared to think beyond modern environmentalism to a future primitive; dared to peel the geopolitical lines off the maps and see watersheds and biomes; dared a politics beyond left and right.

Fifty years is a fairly long time and utterance proliferates but what’s issued from this outfit is durable goods. Planet Drum has been radical, sane, wild and persevering. The bioregional vision is a template for something more than permaculture or restoration or natural history or festivals, although these are all essential to the work. It’s more, Peter said, than “just saving what’s left.”

The synthesis, the understanding, the invitation to a renewal of diversity, wholeness, and belonging in nature—not in general, but in a certain place, respecting its stories, landforms, watercourses and biotic communities have made Planet Drum’s message compelling: the existential meaning of habitat, with the nudge to wonder at and engage with all species— our homies.

Affiliation with Planet Drum and the bioregional movement led me to some of the most enlivening encounters in my life: with magical, charismatic, thoughtful individuals: flocks of terrific writers, gifted naturalists, artists of every ilk; scholars and organizers and shamans, sages and facilitators and cranks; troubadours and comedians, people of first nations, rainbow people, bohemians and cartographers, prairie and savanna and swamp people, city folk and monks, ecofeminists and rural fairies, homesteaders and craftspeople, all bodying forth possibility in their myriad ways. “This is the kind of talent I like to run with,” said Freeman House.

Planet Drum started fresh but not out of nowhere. Shasta bioregion is where I met Peter and Freeman and Judy, the terrain of consciousness that gave rise to one great bioregional cohort. That intelligence kept pursuing leads; going native in the city of San Francisco; journeying upriver and downriver and on around the Pacific Rim, parlaying with others all ‘round Turtle Island.

The core truth animating the forerunners and ongoers is that Earth’s bioregions are immanent: Even altered severely life places abide. Humans can be numbed by consumerism and a host of other grave misdirections, but evolutionary reality is that it’s in our nature to wonder and risk; to know reciprocity with, and care for all our relations. In essence we’ll always be animals, seeking water, sustenance, territory; craving stimulus and medicine: touch, scent, color, vibration, repose; entheogens and herbal remedies; needing Others: prey and predators, symbiotes, coevolutionaries: Kindred; Community. Planet Drum has animated that.

Peter and Freeman left their legacies. Judy remains, works, awes with her grace, wisdom and sheer mettle. Planet Drum endures and inspires. It’s fed souls, gone mycelial, sparked wild pulses of life in a world straying towards zombified gray goo neolife. It’s encouraged life-lovers, place-knowers, sense-makers, reinhabitors and faith keepers; has kept faith with watershed within watershed; kept faith with the seasons and the solstices, equinoxes and phases of the moon.

Gratitude.

Gratitude.

Gratitude.

Stephanie Mills has been writing and speaking for nature and community for nearly 50 years. She is the author of numerous books including Whatever Happened to Ecology?, In Service of the Wild: Restoring and Reinhabiting Damaged Land, Epicurean Simplicity, and On Gandhi’s Path: Bob Swann’s Work for Peace and Community Economics. In 1984, following a life-changing encounter at the first North American Bioregional Congress, Mills quit the San Francisco Bay Area for Northwest Lower Michigan, where she lives to this day.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Jean Gardner – April 11, 2023

Remembering Planet Drum

Remembering Planet Drum, Peter, and Judy supports life today. Cast away any notions of nostalgia! When we bring the past into the present, we are fertilizing our lives now. I have known Peter and Judy since the days when they birthed Planet Drum. Much has happened in the last 50 years that brings to center-stage our awareness of human impacts on Nature. But nothing equals their understanding of the inextricable ties between the natural world of soil, plants, climate, non-human, and human culture.

During the same years Peter and Judy were organizing in San Francisco, I was documenting the presence of the living Earth In New York City. Discovering Planet Drum and their bioregional efforts, emboldened my own work. I also connected with Video Artist Paul Ryan and Cultural Historian and Scholar of the world’s religions Thomas Berry, benefiting from the contributions of both to bioregionalism in and near New York City.

The ground-breaking insights of these four bioregionalists affected me deeply. My life changed. With photographer Joel Greenberg and a foreword by American journalist and political commentator Bill Moyers, we published a book on Urban Wilderness: Nature in New York City. Also, we produced posters and pamphlets on the Urban Wilderness in each borough. We distributed these freely to community organizations, schools, and other local groups to encourage interest in the benefits of experiencing the Living Earth near one’s home.

To this day, I continue my efforts on a global scale now through an NGO I founded to honor indigenous peoples and their fight across the Earth to safe-guard and honor their bioregions.

Jean Gardner is Professor Emerita of Earth History and Architecture at Parsons/New School in New York and is the Founder and Director of Earth Group Global. Jean lives in the Lenapehoking Bioregion. For how her local Bioregion is connected globally see: https://earthgroupglobal.org/2023/03/i-am-haunted-by-waters-by-jean-gardner/.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Brian Hill – April 24, 2023

In the late 1960s and until 1971 I was mostly in New York City at the New School for Social Research studying Cultural Anthropology, teaching at a couple of the local universities and hanging out with political activists and psychedelic groups in NYC. Stanley Diamond was the Chairman of the Department of Anthropology at the New School, and he was friends with Gary Snyder who greatly influenced my Ph.D. dissertation, as did Carlos Castaneda who was a member of our Radical Caucus of the American Anthropological Association. I left NYC in late 1971 and a friend from the Weather Underground suggested I look up Peter and Judy in San Francisco because they were talking about a new effort called “bioregionalism.” At that time new communes were forming in places like Tennessee, Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon, British Colombia and, of course, California. We didn’t know it at the time, but there was a shift from countercultural urban street politics to “living in place,” as Gary Snyder said, and in “re-inhabitation of the land,” as Peter Berg said.

During these years there was great movement among the radicals back and forth across the country. The new communes were networking centers for new views and lifestyles, as well as hideouts for frontline political radicals.

There was great movement and great renaissance. Openness, compassion, unity, trust and sharing all prevailed during these few short years. Bioregionalism was the catalyst that allowed me to transition from being a revolutionary to a back-to-the-land hippie helping to build a new culture that is still being born today. Thank you fellow bioregionalists.

Brian Hill, Bioregional Anthropologist, member of the founding generation of bioregionalists, lives in the Shasta Bioregion. He has specialized the last 50 years as a Back-to-the-Land gold miner and a founder of the now global Alliance for Responsible Mining –https://www.responsiblemines.org/en/, a back country Trinity Alps mountain man, an early 70s cannabis indica farmer, founder of the Wise Use Movement, close colleague of Kurt Saxon who was the founder of Survivalism, a 10-year participant in the 1990s UN NGO grassroots environmental movement, devoted hipneck, a founder of the Back-to-the-Land Project: https://www.facebook.com/ProjectBTTL, and the Counterculture History Coalition: https://chcoalition.org/, and now an ecosystem restorationist helping with the fire and desertification crises that the Shasta Bioregion is experiencing. He’s also trying to link the soil we can make from the forest fuels with the soil regeneration of Kiss the Ground/Common Ground so the 2023 Farm Bill will pass.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Tad Montgomery – April 26, 2023

Judy and Peter were passing through my stretch of the Connecticut River Valley a few years back and had a gig in the small Vermont mill town where I lived. Afterwards I took them out to dinner, up a side street that’s always been a mix of addicts, panhandlers, hippie entrepreneurs, and bohemian artists. We turned a corner and I saw a poet sitting on a stoop. Wheeling the two around to him I asked, “Friend, these two people love the Earth very much. Could you recite your tree poem for them?” He did, a beautiful piece where he talks as a tree might, about to be cut. They were deeply moved, and gave him the kind of recognition that only one poet can give another, an honoring. Then we turned and continued on our way. Peter and Judy each took one of my arms, holding me as we walked up the middle of the street in the summer dusk, and Peter said, “Watch out for him. He’s the type of visionary they go after.”

Tad Montgomery lives in the Connecticut River Valley Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Alice Kidd – April 27, 2023

Planet Drum? What’s it to me?

Planet Drum provided a way into a community of communities. For the communards of the 80s that I lived with, this was a huge gift, to learn of others not unlike us.

We lived in the edge of the wild, and all of the writing about bioregions was both supportive and fascinating.

And the people we met and heard about. Suddenly the world was far more inviting. And so many of them understood community. And they, like us, believed in the necessity to re-build culture.

And now, as we work to explore possible futures locally, I am finding what I have learned through bioregionalism and with others is very valuable.

So yes, I celebrate Planet Drum.

Try to remember the first time you heard about human exceptionalism and the need to re-join the natural world. Or the first time you heard about local solutions. Or the first time you got obsessed with local maps. I did all of those things either because of the work of Planet Drum and others … or with people I met through them. And they know a lot of great people and communities.

And it was like a smorgasbord – my choices, my consequences.

Going into an unknown future requires working with people you do not agree with (or like or trust). And yet, if you do not know what will happen, you have to include the possibility that you and the people you agree with (and like and trust) have got it wrong. So, you have to figure out how to stretch across the divides. The first rule is that no-one is perennially in charge. And you learn how to listen, listen, listen.

Planet Drum models that. They share what they have learned; they work on their own projects; they offer educational events and publications; they find and work with each new generation in their bioregion. And they do not tell us what to do.

Judy Goldhaft reminds me of a “Mother Tree.” She is totally herself, a dancer, actor, and writer. At the same time, she nurtures the people she works with, of all ages. (We have one of those in this community).

Peter was a character. Each of us knew a different Peter. He helped a very nervous not quite poet to perform at a bioregional congress evening event. He taught me things about my poem that I had not known. And if you got him talking about bioregionalism, he was one of the best thinkers I know. His love for the ideas shone through.

50 years is a long time (I know, I’m 74). To reach this point in such good health is a major accomplishment for organizations, and humans. Thank you to all of you for your work and your vision.

Witten in 1987, I have included the poem that I read at the third bioregional congress held in Squamish in 1988:

Pain

I know the colour of pain

I know of its necessity

not because we need it to grow

but because it happens as we grow.

It is a feature of life.

But we must take care not to worship it.

It lets us know we are alive

but so do laughter, joy, delight.

It etches the faces of my friends

and burdens not a few.

We, so passionately devoted to change,

Inspired by the vision of a new world, new culture

are not strangers to it.

Pain limits

We can go here – and no further.

It directs

not this way folks.

Engaging vigourously with life

brings intimate acquaintance with pain.

It takes time to learn to withdraw the foot

from sharp stones – before they cut the flesh.

It takes time to learn how to share

without overpowering the other

with fitting generosity.

We live with pain

as we live with our friends

An intimate.

In time it may become a respected tool

The first warning signal shapes our footsteps.

Alice Kidd is an adult educator and community activist living in the Dry Interior Fraser River Valley Bioregion in British Columbia. This includes the town of Lillooet and the Yalakom valley 20 miles away. In 2020, she wrote an article titled “Notes from the MidFraser” in Planet Drum’s Pulse publication.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Jacqueline Froelich – May 1, 2023

May Day Froelichian Planet Drum Memory

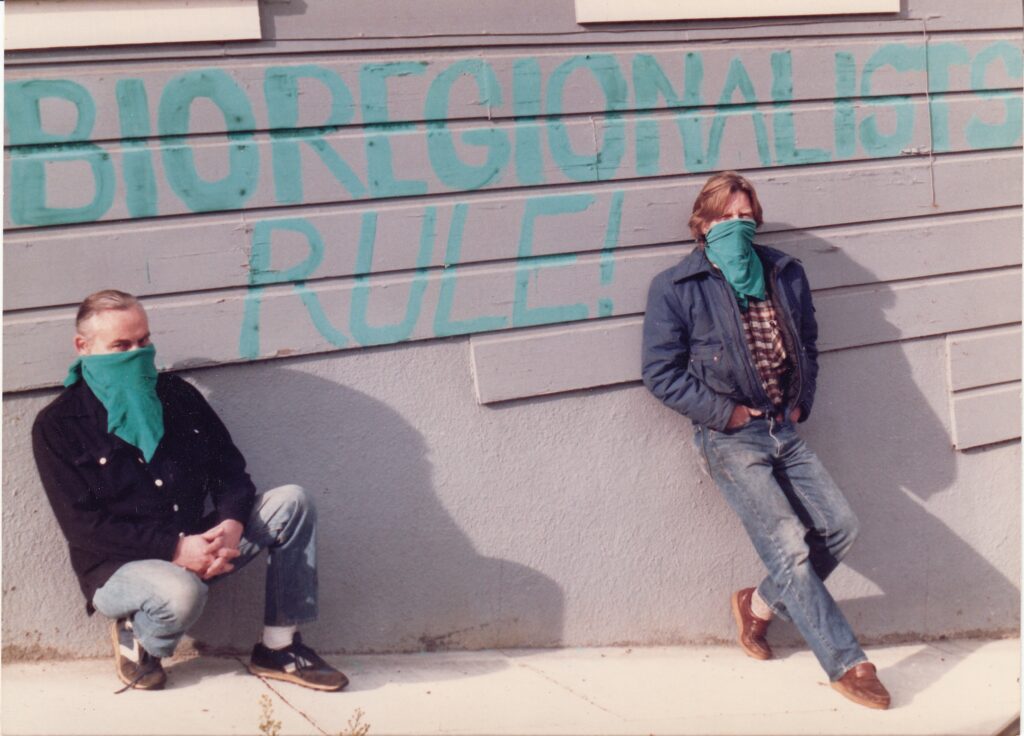

Circa 1990 I was a forest-dwelling Ozarkian offset lithographer, taking leave in San Francisco’s Mission District for a spell to work on some ecological communications projects. I convinced a bioregional colleague (whom shall remain anonymous) to join me in committing a crazy act of guerilla graffiti on Planet Drum’s residence/offices occupied by the most elegant Judy Goldhaft and brilliant bioregional theorist Peter Berg — with whom I had congressed for several years. We hopped a trolley late one evening, wearing dark clothes, packing water-based paint and brushes. At our destination, when the coast was clear we painted in large letters:

BIOREGIONALISTS RULE!

To this day I regret this act of vandalism, and should have returned to repair the damage. But I was a young eco-punk spurred by retribution, I think, because Peter for some reason, enjoyed teasing me at bioregional congresses, where I and a gang of writers during the halcyon North American Bioregional Congress (NABC) era worked day and night publishing our congressional minutes, documenting all-species resolutions and green laws and producing bound NABC proceedings.

We legacy bioregionalists were and remain a brilliant band of Earthists, still working in the trenches in all sorts of profound capacities, despite a looming climate catastrophe wrought by 8 billion + humans. We did our best.

Thank you, Judy and Peter and Happy 50th to Planet Drum!!

Jacqueline Froelich is an NPR-KUAF Reporter and Ozarks Area Community Congress Bioregionalist.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Beatrice Briggs – May 2, 2023

My First Encounter with Planet Drum

Once upon a time in the early 1980s, I heard about the concept of “bioregions” from Thomas Berry. I was living in Chicago at the time and soon connected with David Haenke and Stephanie Mills, both luminaries in the Great Lakes region. In this good company, I began to apply the bioregional concepts in my home place. Then I decided to convene a one-day workshop that would bring together people knowledgeable about the prairie, the lakes, and the rivers that defined what we were beginning to call the “Wild Onion Bioregion.”

By that time, I was dimly aware of the distant beating of Planet Drum. One day I called the office in San Francisco to ask about the availability of information to share at the upcoming workshop. To my good fortune, Peter Berg himself answered the phone. It is hard to say who was more surprised – me to be in direct contact with one of the legendary founders of the bioregional movement or Peter talking to an unknown yoga teacher in Chicago.

Over the next several years, Peter and I had numerous opportunities to meet in person and collaborate, but I will always be most grateful for his willingness to help me find my way on the bioregional path.

Beatrice Briggs is the Founder and Director of the International Institute for Facilitation and Change (www.iifac.org) 2004 – present. She is a specialist in participatory processes that help visionary leaders and change-oriented groups define their goals and collaborate to make a significant difference in these challenging times. A native of the USA, Bea lived in the Wild Onion Bioregion (aka Chicago) before moving to the Bosque de Agua (Water Forest) in central Mexico in 1998.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By David Haenke – May 2, 2023

When Planet Drum Came to the Land of the Oak

From the time the first Ozark Area Community Congress (OACC), henceforth referred to as “Oak,” had its acorn emergence from the Dream of the Earth in October 1980, I feel we were fully in this Dream when Oak II leafed out a year later at the sacred Alley Spring on the Jacks Fork River near the confluence with the Current River Watershed, with the miraculous appearance of Planet Drum in the quintessential foundational representation of Peter and Judy and delegation from the Shasta Bioregion!

Planet Drum! Planet Drum! The first time those two words appeared to me in the middle-ish 70’s they struck my being like a synesthetic tuning fork that has never stopped humming and thrumming to this day. Planet drumming out around sweet Earth, bardic music in the key of Gaia, Schumann Resonances, mothered by lightning mind on oceans of foundational alpha waves the length of the circumference of Earth, nascent biocentric mind in evolution…Shasta quantumly entangled with Ozarks: bioregionalism!

Ella Alford (supporter of bioregionalism and namesake of The Alford Forest, the 4,300-acre ecological reserve that she donated to the Ozark Land Trust, the Forest hereabouts within and along the Bryant Creek/Watershed) funded Judy and Peter to come to Oak II. Ella attended with her beloved dog Buddy.

Oak II was in so many ways a wondrous one-off, a full campout at Alley Spring Park. 175 people, somehow fed off a wood cookstove I schlepped in my truck, with giant pots of beans and rice to simmer on the stove, and other donations of comestibles from gardens and anon. We had the simplest of “infrastructure,” with the main venues being a big rented auction tent, the picnic tables of the camp, grass and trees to meet upon and under, plus tents that folks brought for their lodging. Water sources included a hose I brought and hooked up to a camp hydrant, the river, and frequent rainstorms. The full cost of attending, including food, for the three days was $10.

Attendees/Representatives came from all around the Ozarks, and other realms of Turtle Island. It was so phenomenal to have Peter and Judy there!

Oak II, like Oak I, had its time from Friday through Sunday divided up in three primary modes: full group/plenaries held in the big tent, committee meetings in the tent or outside, and workshops. Along with his talks on Planet Drum and bioregionalism in the tent, Peter also reported on his attendance at the first meeting of the Fourth World Assembly in London in an outdoor committee session where we discussed what might be next for the bioregional movement. In that session, I brought up my resolution that had passed at Oak I on convening a “congress of congresses.” The discussion continued with my proffering the name “North American Bioregional Congress” (NABC). All in attendance agreed that this sounded good. Later the Oak II plenary approved a resolution to allow me to go forward in working on convening what became NABC I three years later in 1984. In Oak II’s wondrousness, Planet Drum/Peter and Judy were present in catalyzing NABC I as a manifestation of at least some dimensions of Peter’s visionary declaration, “Amble Towards Continent Congress,” written some years before in 1976.

Oak II, through the inspired attendance of a contingent of folks from the Kaw River Watershed, also led to the founding of the KAW Council in 1982.

I believe Planet Drum’s presence at Oak II was a primary event in the story of the unfolding of the bioregional movement and on to its continental manifestations. All gratitude to Planet Drum, Judy, the memory and legacy of Peter Berg, and the people of the second Ozark Area Community Congress!

David Haenke is co-founder of the Ozark Area Community Congress which will gather for the 44th year this October. He lives in the Bryant Creek watershed in the Ozarks Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Eve Quesnel – May 3, 2023

Some quotes by Peter Berg:

“All life on the planet is interconnected in a few obvious ways, and in many more that remain barely explored. But there is a distinct resonance among living things and factors which influence them that occurs specifically within each separate place on the planet. Discovering and describing that resonance is a way to describe a bioregion.”

“Bioregions are geographic areas having common characteristics of soil, watersheds, climate, and native plants and animals that exist within the whole planetary biosphere as unique and intrinsic contributive parts. Consider them as possessing the diverse and necessary distinction of leaves from roots, or arms from legs.”

“The main focus for life-place learning is on the ecologically bounded place itself. It isn’t difficult to locate this spot. Identify the climate, weather, landforms, watershed, predominant geological and soil conditions, native plants and animals, and sustainable aspects of the traditional culture along with ecological practices of present day inhabitants. Your life-place is the geographic area where those things converge.”

“The bioregional perspective…recognizes that people simply don’t know where they live. Generally when you ask people what their location is, they give it in terms of a number on a house on a street in a city in a country in a state in a nation-state in some political division of the world. But if you were to answer in bioregional or ecological terms you might say, ‘I’m at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and San Francisco Bay in the North Pacific Rim of the Pacific Basin of the planetary biosphere in the Universe.’”

Eve Quesnel is the co-editor of The Biosphere and the Bioregion: Essential Writings of Peter Berg and is retired from teaching English at Sierra College in Truckee. She lives in the Sierra Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Ken Lassman – May 4, 2023

I have struggled to find words for the handful of times I really got to spend some good time with Judy and Peter, and I think I have finally figured out why that is. In the early days of organizing the first few Congresses, I was a young man from rural Kansas who had not been exposed to much outside my own circle of friends and strongly held beliefs that were all pretty much coming straight from my experiences with the land around me, supplemented by my voracious appetite for those who had things to say about such things.

When I stumbled across Peter’s “Amble Towards Continent Congress” in Truck 18 Biogeography Workbook (1) put out by David Wilk, I was blown away. Here was someone who had their pulse on the planet in a way that I had not seen so deeply before. When the first North American Bioregional Congress convened in Excelsior Springs, MO and I got to meet Peter and Judy for the first time, and to see Judy’s jaw dropping dances, they were like gods to me. I was star-struck. I was happy to just be in their presence. Seems kinda silly I suppose, but that is pretty much the honest-to-god truth.

Over the years, that relationship has matured considerably and even from afar, took on a much more in-depth form as I continued to read and share their many exploits through their Planet Drum missives, visiting them, and seeing them in subsequent congresses. But the aura of being beings from a slightly more elevated plane than others I have known persisted in the back of my mind, if I am honest with myself. I attribute my speechlessness so far to arising from this place, and it’s something that I feel I can contribute to honoring them.

Ken Lassman is an ecological writer and author of Wild Douglas County (2007) and Seasons and Cycles: Rhythms of Life in the Kansas River Basin (1985). He is co-founder of the Kansas Area Watershed (KAW) Council which explores, protects and celebrates the prairie and local culture through gatherings, educational programs, creativity and creative thinking, and the occasional journal Konza. He also curates the weekly nature postings found at www.kawvalleyalmanac.com and has been married to poet and author Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg since 1985. He is a fifth-generation resident of Douglas County in the Osage Cuesta ecoregion in the Kansas Prairie Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Glenn Page – May 9, 2023

Congratulations Planet Drum for this historic milestone of 50 years of providing inspiration towards a more just, equitable and regenerative world. Here in the Gulf of Maine, one of the most rapidly warming systems on the planet, we are inspired by the legacy of bioregionalism to learn from the past, better see the current realities and help navigate into the uncertain future. Thanks to the work of Planet Drum, we are better able to see interconnected systems across our biosphere so that we can explore the “terrain of consciousness” that inspires us to become better stewards. Your legacy has inspired us to examine linkages, cross-scale dynamics, traps, tipping points, governance dimensions, and transformation systems where climate and sustainability actions can be suitably amplified, scaled deep and wide as we face the growing polycrisis. We must continue to build on the legacy of Peter Berg and Raymond Dasmann to learn-by-doing, weaving stories of collective action that document enabling conditions and bust open windows of opportunity. Promising signs of bioregional governance are emerging across the globe and serve as evidence of the legacy of Planet Drum. We send deep gratitude for the beat of Planet Drum and what that has done, and will continue to do, to inspire a global revolution!

Glenn Page is the Founder of the Collaborative for Bioregional Action Learning and Transformation (COBALT) and lives in the Casco Bay area located in the Gulf of Maine Bioregion.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Amy Berk and Cheryl Meeker – May 15, 2023

As artists, activists and educators based in San Francisco, Amy Berk and Cheryl Meeker are committed to showcasing the groundbreaking work of Planet Drum on their 50th anniversary. Although we have not known about them for long, we are blown away by their prescience and connection to integral art movements of the last 50 years. The creation and mailing out of their signature “bundles” is of particular interest. In addition to their form as mail art, the collaborative creation of each bundle brings together a variety of voices and involves a broad community, de-emphasizing the lone individual authorial voice while uplifting and empowering the communal. The bundles, made up of poems, drawings, maps, photographs and books in differing combinations show great attention to conceptual integrity, much like how a bioregion is a distinct area with coherent and interconnected plant and animal communities, and natural systems, often defined by a watershed. The bundles are connected through content, and intent and serve as “life-place(s)” for human interactions, connections and community. The work of Planet Drum intersects as well with the art of the archive, event and process-oriented art, social practice, activist art, as well as pedagogical and eco art.

Amy Berk is an artist and art educator who taught at the San Francisco Art Institute since 2006, serving as Chair for the Contemporary Practice program from 2011 to 2013. She directed the award-winning City Studio program which engages underserved youth in their own neighborhoods through sequenced art classes that are both rigorous and joyous. In 1996, she co-founded the innovative Meridian Interns Program serving inner-city teens and has taught in the Post-Baccalaureate program at UCBX since 2004. She has shown her work internationally, was one of the founders of the web journal stretcher.org and the artist group TWCDC.com. Since 2019 she and Chris Treggiari have collaborated on ARTIVATE which creates opportunities for youth to explore artmaking and citizenship in the public sphere. Amy has recently taken on a Program Director role at Industrial Design Outreach and is running a mentor-driven project creating light sculptures at Academy High. She remains committed to giving teens (and adults) a much-needed voice, a safe place in which to speak and helping them find the proper tools to do so. She lives in San Francisco, the unceded ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples, in the Bay/Delta Bioregion.

Cheryl Meeker is a visual artist based in San Francisco, the unceded ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples, in the Bay/Delta Bioregion. Her work ranges from photography to installation, drawing, painting, archives, video, interactive web projects, and social sculpture often touching on the fundamentals of sustenance in our environmentally destabilized world. A founding member of Stretcher.org, she has frequently collaborated with artist Dan Spencer as the art team Dan and Cheryl, producing actions, panel simulations, and video. Her ongoing activism with the housing and climate justice movements and recent work in the public library system inform her approach. She was one of the organizers of “Capitalism Is Over! If You Want It,” and her work has been exhibited at ATA, Mission 17, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Southern Exposure, the Oakland Art Museum and online at SFMOMA project open space and the Richmond Art Center. Her writing has been published in NYFA Current, Stretcher, and Art Papers. Find further information at https://cherylmeeker.blogspot.com/

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Craig Dremann – May 25, 2023

What I remember the most about what Peter said, was when we were sitting around the kitchen table and he was giving an example of how we need to go “All-In” with our work with conservation and repairs to the environment.

He was giving an example of a person picking up plastic cups off of a park’s lawn. What Peter said, was “Why plastic? Why lawns?” That has always stuck with me.

Craig Carlton Dremann’s Native heritage comes from the Tuscarora Nation and he started the “Redwood City Seed Company” 51 years ago, to offer traditional and heirloom vegetable seeds. In 1992, he started “The Reveg Edge” to restore grasslands and wildflower fields, with 800 acres restored so far—visit Kite Hill Wildflower Preserve in Woodside, CA to see wildflowers blooming from March to October each year. Between 2002 and 2010, he worked with the Saudi government, that resulted in 500 million acres being set aside as Ecological Restoration Preserves—the world’s largest Global Warming carbon sequestration project, being planted with one million trees per week as the “Saudi Green Initiative” until one billion are planted in total. This project was expanded to include 24 countries under the “Middle East Green Initiative” to plant a total of 50 billion trees. Craig is a very grateful resident to be able to live on the Lands of the Muwekma-Ohlone Nation within the San Francisquito Creek watershed of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By David McCloskey May 27, 2023

This first piece is the eulogy I originally wrote for Peter on August 20, 2011.

On Peter Berg’s Passing….

The eulogy from Planet Drum was wonderfully evocative….

I have only a few comments to add. First, what struck me most when meeting Peter the first few times was his audacity, his grinning energy, his courage in taking a unique stand, and the incisive clarity and conviction of his thought. Wow, when he launched into those critiques of global industrial monoculture and the bioregion as the place to decentralize to, “the elsewhere of civilization,” I sat up and listened hard–he got me right away.

Of course, I loved his “mapping your bioregion” workshops with the Luminous Judy Goldhaft and her tremendous “Water Web” dance. They inspired me to begin working on mapping watersheds and Ish River Sound and Cascadia. Peter was also a better writer than people recognize.

One minor correction: to my knowledge Peter was not the first to coin the term “bioregion”–that honor goes to the obscure inventor Alan Van Newkirk of Canada. Peter may have been the first to coin the key term “reinhabitation,” though I don’t know who invented what in that fruitful collaboration with Ray Dasmann.

As far as I know, Peter was the first to link bioregion, a version of the biogeographical province, with human culture as a “terrain of consciousness,” a landscape of human perception, joining meaning to value. Linking ecosystem to region to culture and perception is an achievement of the first rank. This still distinguishes bioregions and bioregional mapping from all other “ecoregions” and “ecozones.”

But there’s something else still, a little harder to put one’s finger on. How and why and when did Peter Berg have the epiphany, the felt transformational insight, that the existential key is PLACE!!??? Not abstractions like Environment nor Ecology, nor–nor–or etc., but the living breathing place? Peter felt in his bones that the “earth is alive,” and the face of the earth that we inhabit is the place itself—the life-place, our homeplace. Perhaps it was a translation of the ecological notion of habitat, or some other electric source, but opening himself to the reveal of this fundamental truth transformed his life and ours.

Today we need to recover both the notions of reinhabitation and bioregion from an overly localized notion of life-place, and embrace our wider regions as living places, such as Cascadia…. enter into the full range of all our bioregional addresses … and recovery of the “forgotten country” in-between….We need to engender a deeply rooted “culture of place”

on all levels….

I stand in tribute and do a waterfall dance for Peter Berg, Judy Goldhaft, Freeman House, David Simpson, Stephanie Mills, and all the other pioneers of bioregionalism!

——-

This next piece was written on May 27, 2023.

On the 50th Anniversary of Planet Drum: In Honor of Judy Goldhaft

Judy Goldhaft is a luminous being….

There’s a glow about her… and a lightness of being that befits a dancer…

She exudes a warm welcoming open presence that invites others to bloom like her….

Planet Drum has always been a collective communal project, but she has been the heart and soul of the bioregional movement. As a “Jill-of-all-trades” behind the scenes, she has kept the office, and Raise the Stakes, and latterly the Pulse and website, going. She’s also a consummate editor and publisher. Quite literally she is the matrix, the connecting thread, that keeps it all going….

She embodies moral clarity, compassion, patience, and understanding. She is infinitely “hip” in the original sense, “getting things” intuitively from the inside—poetry, arts, music. Her own “Water Web Dance” is a true bioregional gem, enacting in graceful flowing movement and poetic image what “watershed consciousness” means.

How her circle and generation came up with “bioregionalism”—what grounded inspiration led to this epochal fierce and beautiful philosophy of place-based reinhabitation and restoration as “The Real Work” of our time—and how they found their way and so creatively blazed the trail—remains an unexplained miracle, something for ecocultural historians to ponder…. But one thing remains clear: she exemplifies the best of bioregionalism—and its original promise–in her life and work.

It has been my pleasure and honor to have known and worked with Saint Judy the Goldenhearted!

David McCloskey lives where he was born in McKenzie-Willamette land, foothills of the Cascades of western Oregon … Kalapuya “Illahee.” An Emeritus Professor from Seattle University, he’s considered “The Father of Cascadia” having created the idea of “Cascadia as a BioRegion” in 1978. He’s mapped the distinctive character and context of Western bioregions for over forty years, including the original hand drawn “Cascadia” map (1988) from which all others derive, updated in the award-winning GIS-based “Cascadia: A Great Green Land” (2015), an “Ish River-Salish Sea” map (2022), and the second edition of “The Cascadia Map-Atlas” (late June 2023). His “Ecology & Community: The Bioregional Vision” (w/ a centerfold map of “The EcoRegions of Cascadia”) appeared in Columbiana in 1994 and was distributed as a bundle by Planet Drum. He’s created an original BioRegional Mapping Model which appeared in the Pulse, as well as numerous ecocultural, philosophical, and poetic pieces (e.g. in the forthcoming two volume “Cascadian Zen” from Watershed Press). To learn more, go to cascadia-institute.org, and to order his maps go to featheredstarproductions.com, then open “Map Gallery.”

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Denise Vaughn – May 28, 2023

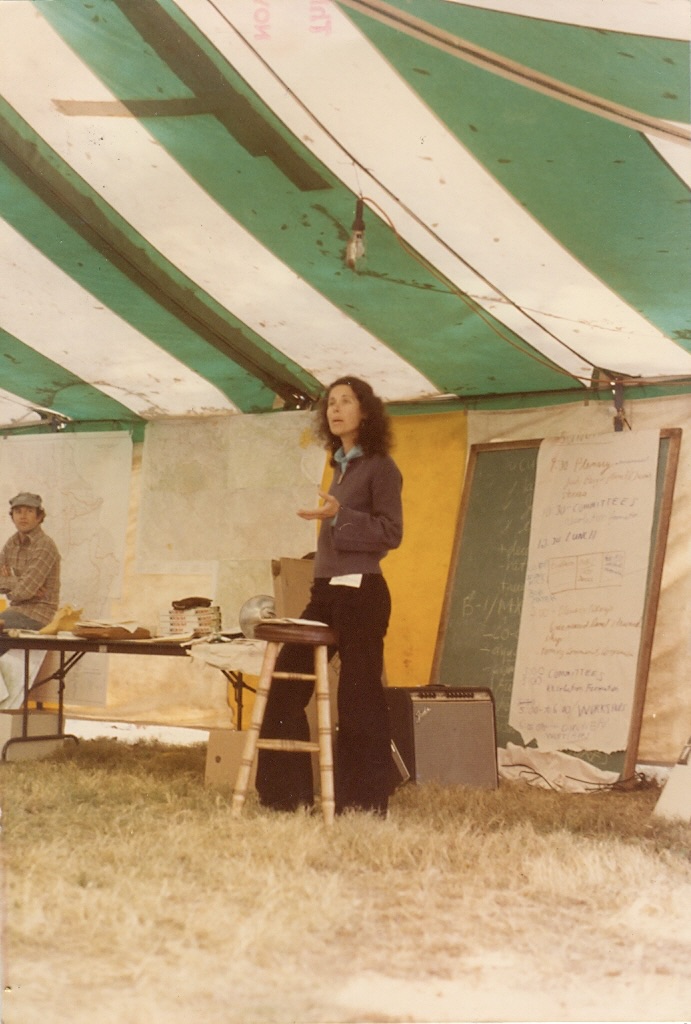

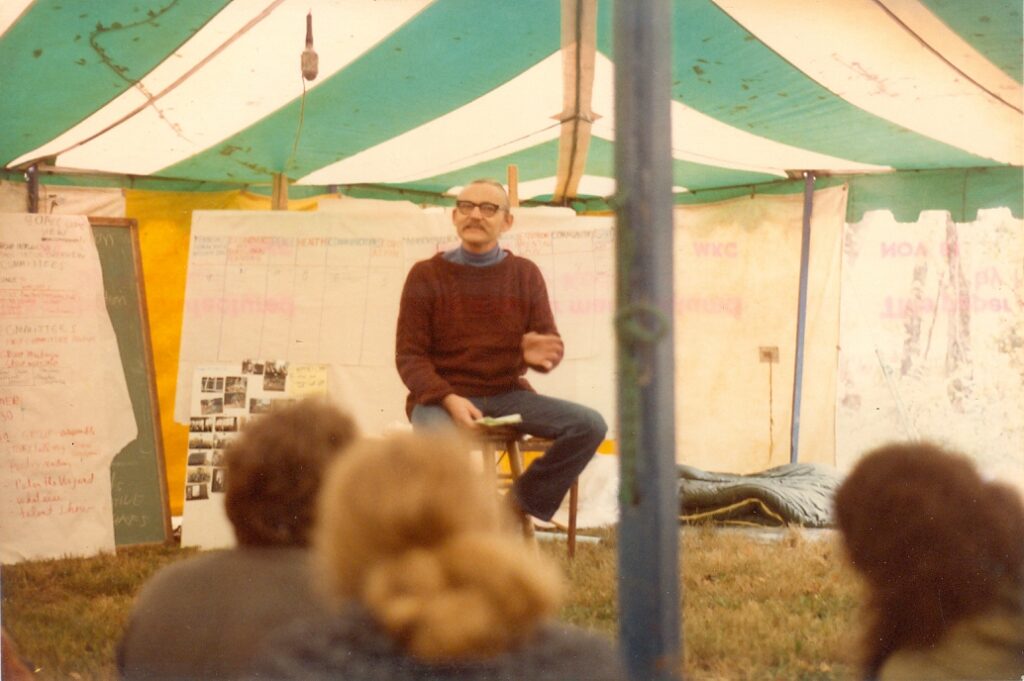

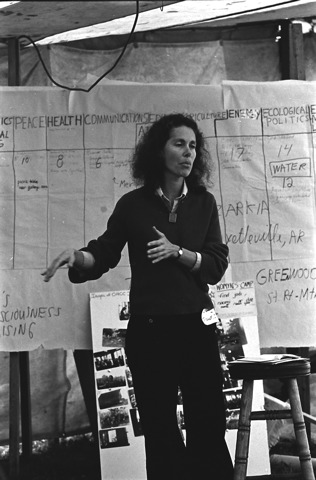

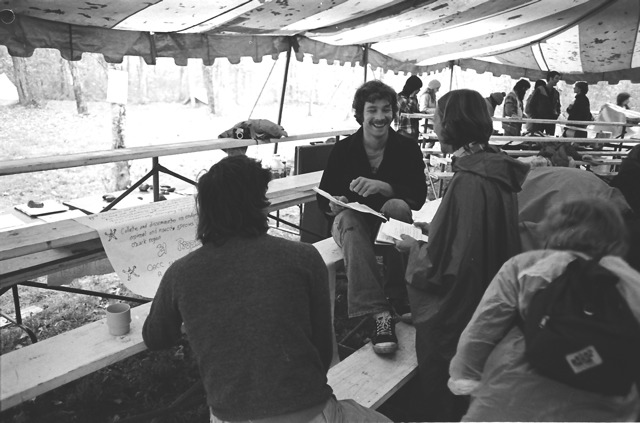

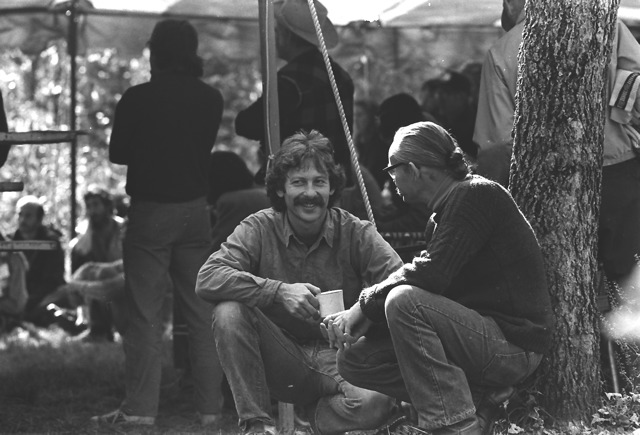

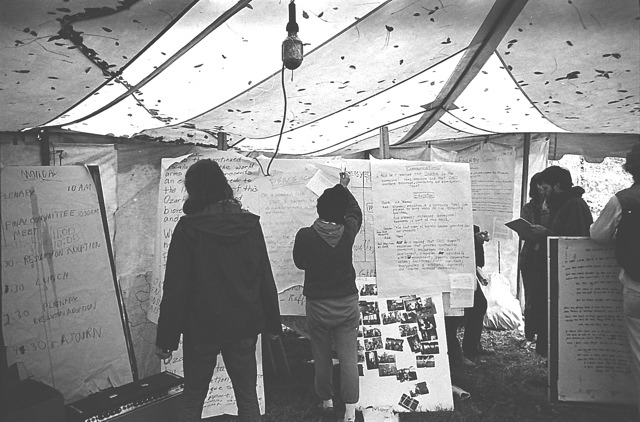

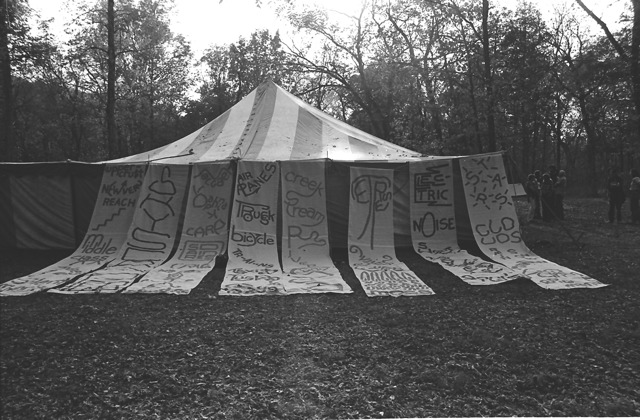

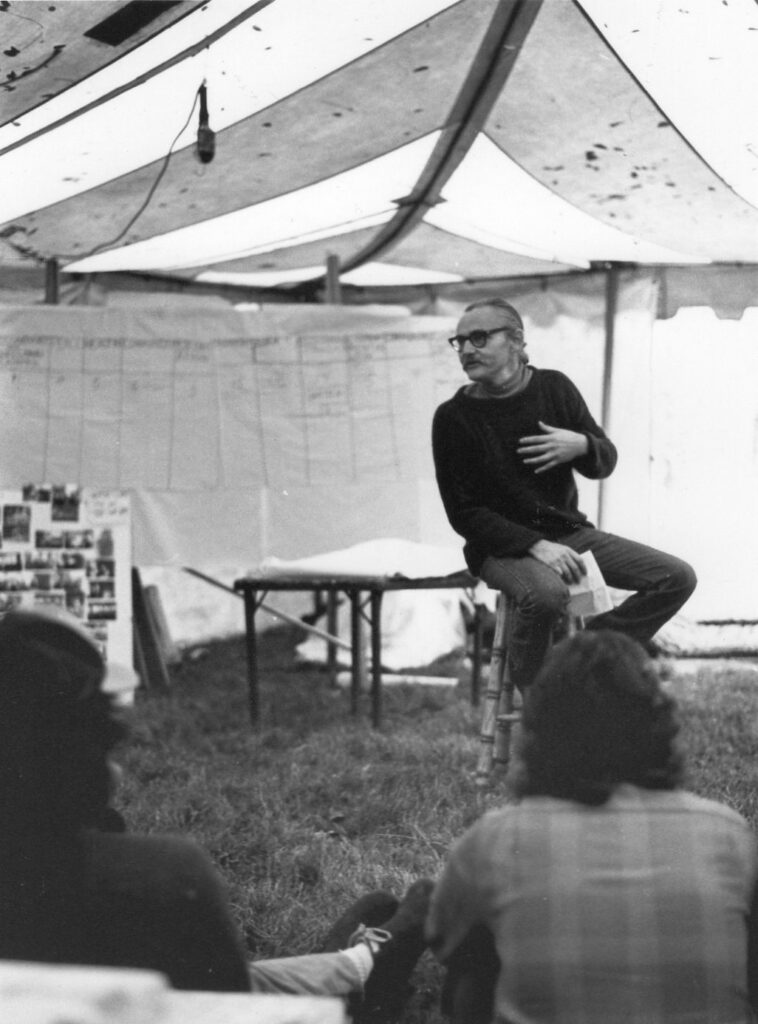

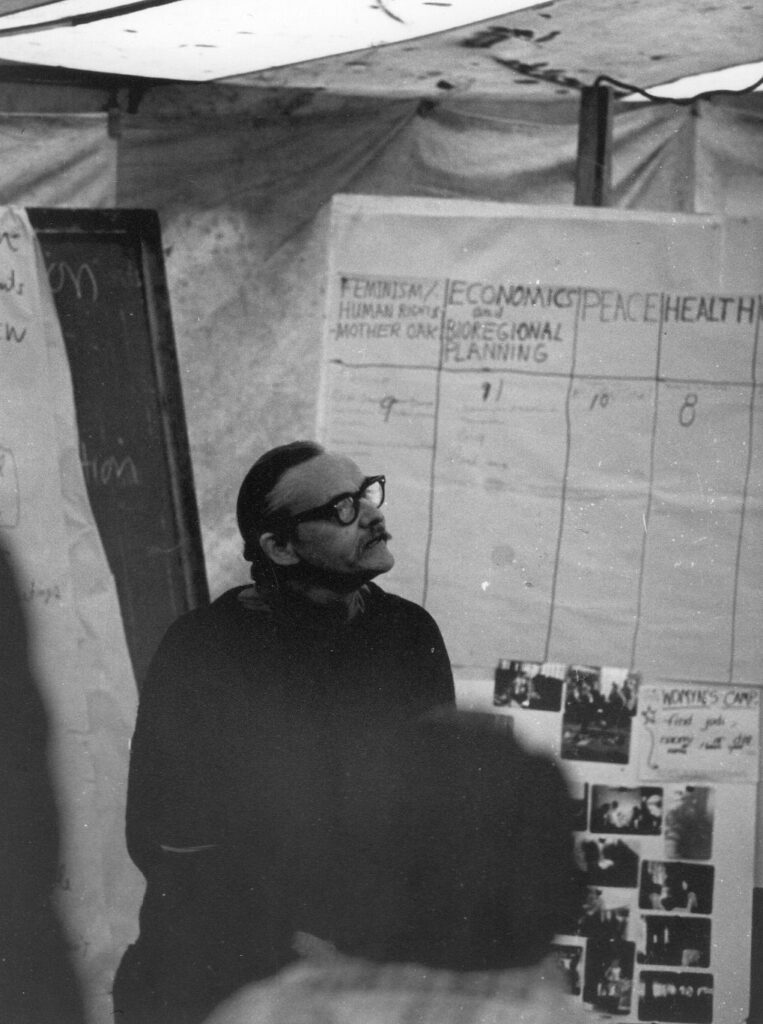

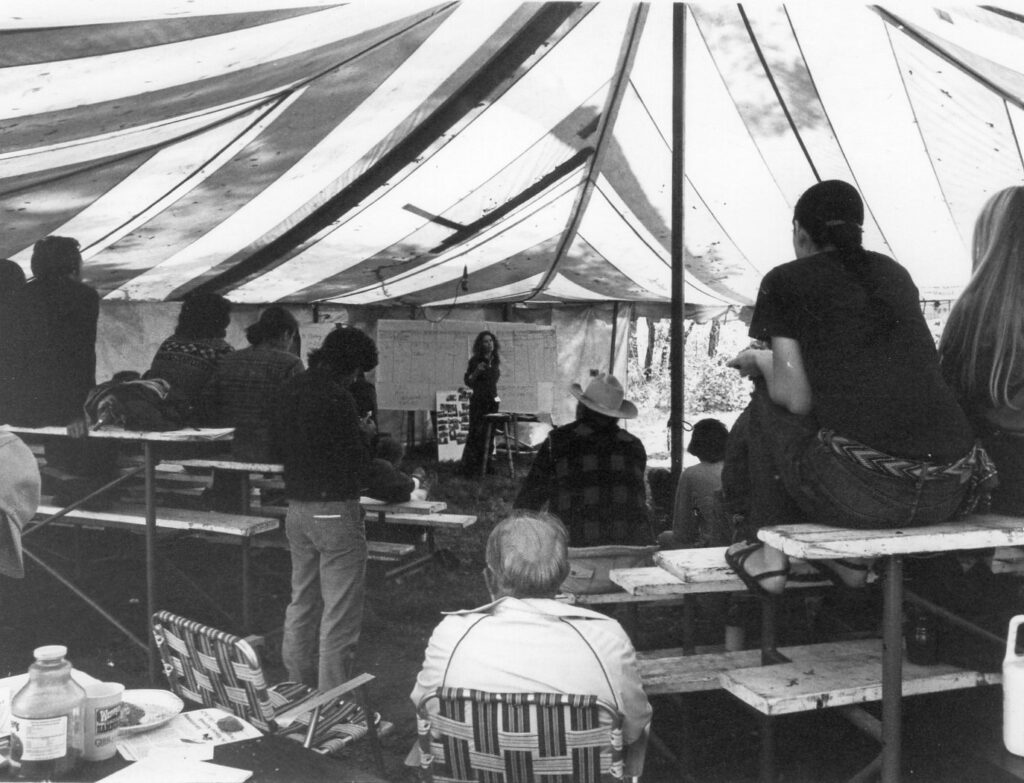

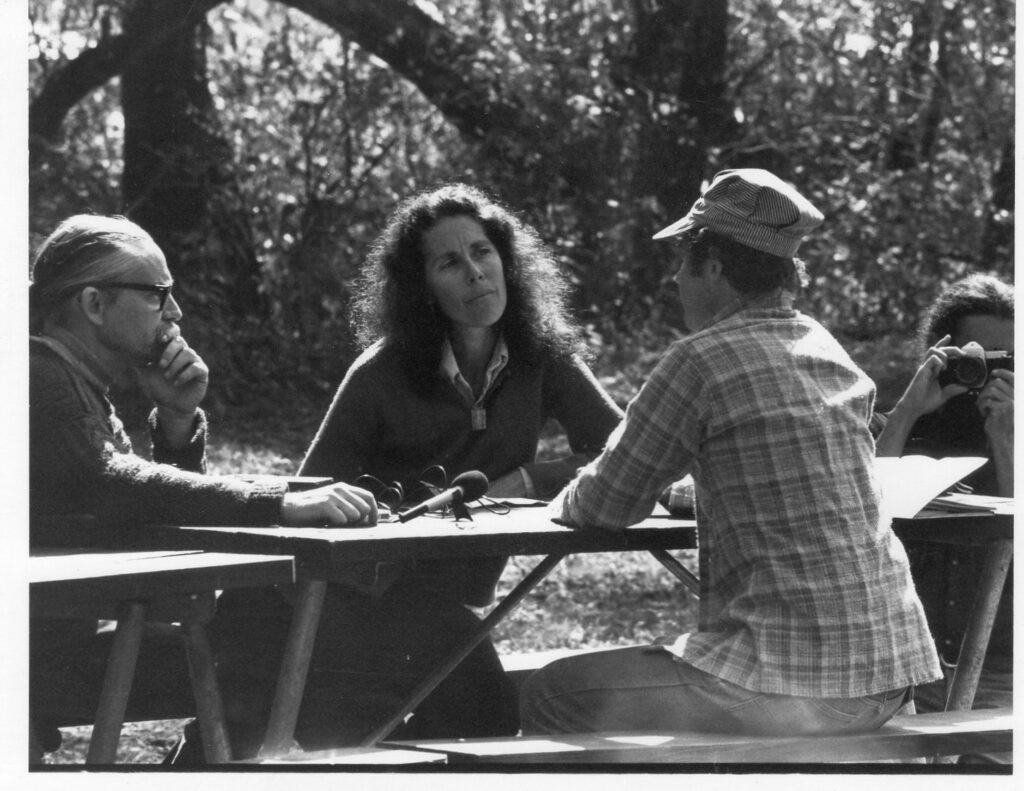

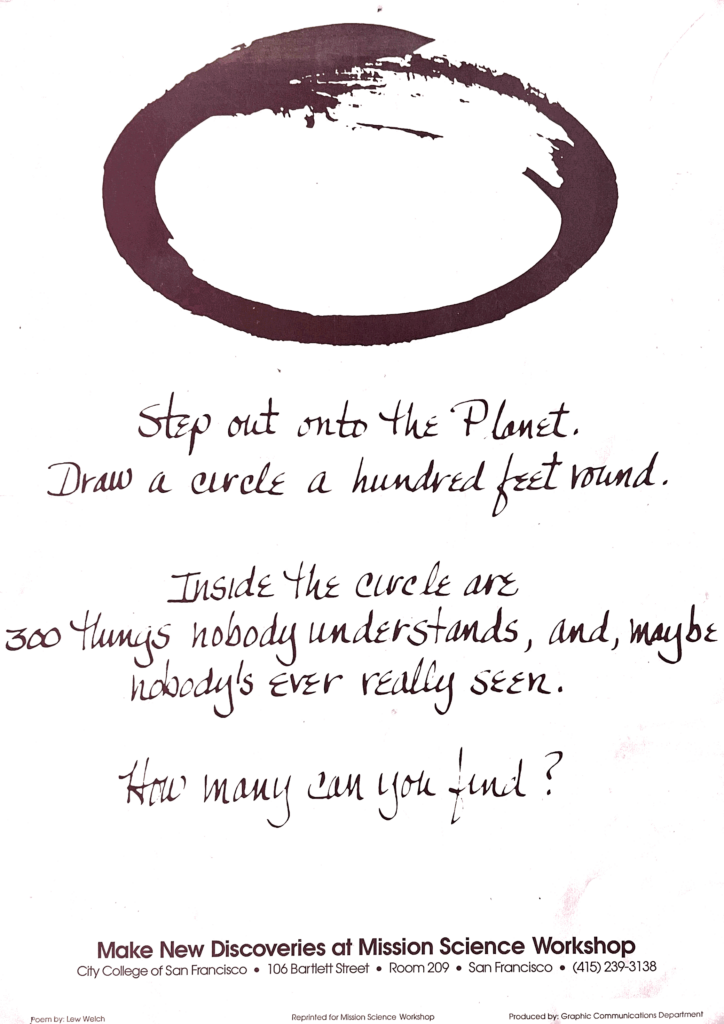

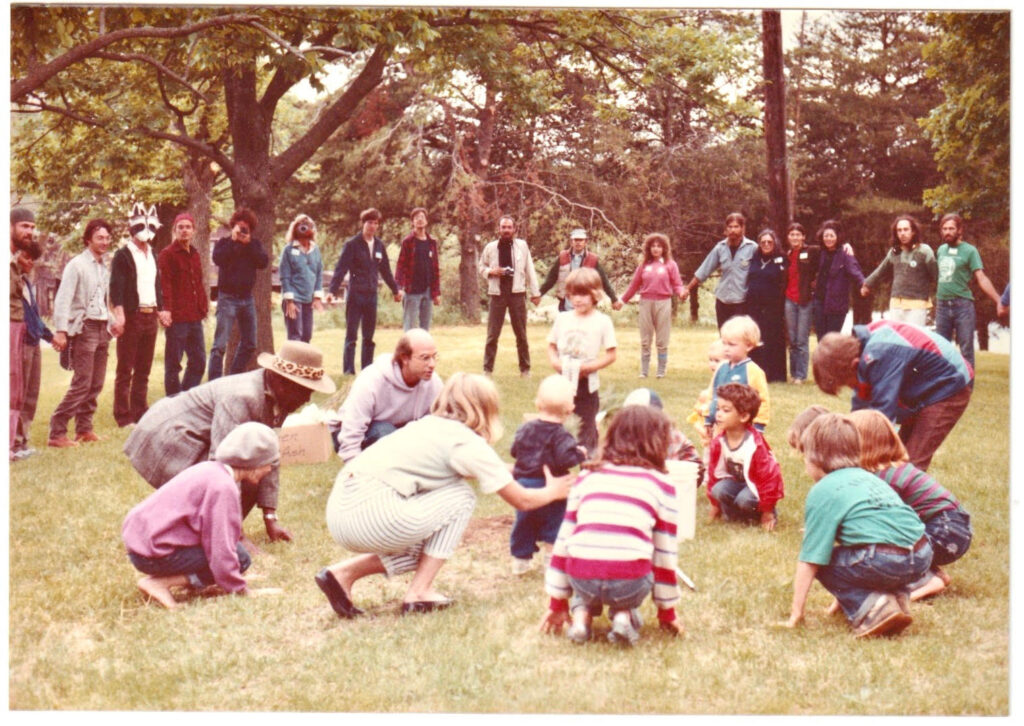

Included here are photos from the archives of the second Ozark Area Community Congress (OACC) held in 1981. That year, the OACC took place at Alley Mill Campground along the Jacks Fork River in the Ozark National Scenic Riverways (National Park). We rented some big tents and had an all-outdoor event. The photographer was Phil Orlikowski.

Denise Henderson Vaughn is a longtime co-coordinator of the Ozark Area Community Congress, which will gather for the 44th year this October. She lives in the Jacks Fork watershed in the Ozarks Bioregion. She will travel to D.C. in June of 2023 for the Smithsonian Festival on the National Mall where she will help OACC co-coordinator Sasha Daucus to showcase the Ozarks Seasons poster that was created nearly 40 years ago with inspiration from Planet Drum bundles. You can read more about and order the poster here: https://ozarksresourcecenter.org/seasons-poster/.

<<<<—————–>>>>

By Chris Carlsson – May 28, 2023

A Green City?

San Francisco is probably a “greener” city today than it has ever been since the beginning of urbanization in 1849. There are more street trees and more park land. There are wildly successful restoration projects in the Presidio’s El Polín watershed and along Mission Creek (and more to come in India Basin and Yosemite Slough), which combined with the City’s Department of Environment Natural Areas Division are giving the original web of life on our tip of the peninsula a real shot at renewal. None of this was true 50 years ago when the Planet Drum Foundation was founded. The Bay itself is probably less toxic than it has been in decades, thanks to the Clean Water Act and countless billions spent on sewage treatment. The stunning clarity of the skies during the Covid lockdown was a revelation, proving that we CAN stop this madness and—though we have failed to take advantage of it this time—reorganize and change how we go about making life together.