The Post-Environmentalist Directions of Bioregionalism a lecture by Peter Berg given at the University of Montana, Missoula, April 10, 2001.

The central subject I’m going to be talking about is the biosphere, the thin skin of life that surrounds our planet. A very thin covering, like our own skin. And the question is: how do we biosphere? It sounds like a verb, doesn’t it? This is an interesting idea for two reasons. One is that we’re all coming out of the industrial era beginning from roughly the 17th century to the present. We’re at the beginning of late industrial or even post-industrial society. The second thing is that biosphere in the sense of “the blue planet” seen from space, is a relatively new idea. It’s not exactly the same idea as the older sense of Mother Earth. For example, a Hopi or Navajo representation of the universe would be from the Southwest Desert. Navajo sand paintings are done on sand, they’re not done on Everglades muck. That’s a local-cosmological vision of Mother Earth. But a planet-wide biosphere is a somewhat different concept.

There is a potential for some major considerations that can come into play when you begin thinking about the fact that we all share the earth together. One is that we are a species. Homo sapiens is a mammalian species. We are animals. The other forms of life that we share the planet with are similar to us in many ways. We evolved in the biosphere, we weren’t spirited down from a spacecraft to colonize Earth. We are interdependent with all the other life forms and forces on the Earth. Which even includes interdependence with fleas and scorpions.

How does one grasp this? Well, it’s not easily graspable. It’s not the same kind of thing as knowing what’s happening on channel four. Take as an example the nitrogen cycle. We know that the nitrogen cycle is active in the biosphere, we know that in fact that we participate in the nitrogen cycle. The nitrogen cycle is one of the most important gaseous phenomena in the biosphere, but we don’t know exactly how it operates with us in this room right now. It’s necessary to have a little faith about this. We’re not going to know what happened with everything we eat or where everything we eat goes. Or what happens with all of the elements that move in and out of us. The exact nature of our total interdependence with natural systems in the biosphere will remain a large-scale mystery.

Another aspect of being in the biosphere is that you have to be some place. This has sometimes gone right by people who are involved with environmental causes. Environmentalism has largely been an activity that was parallel to industrial society, which is essentially dislocated. All of us at every moment are some place in the biosphere, a bioregion. You may have noticed, in just the last ten years, that most major ecologically oriented organizations have begun to fit the notion of a biogeographic region into their programs. The Sierra Club, possibly one of the most conservative environmental organizations, has been persuaded by its membership to start an ecoregion program. It is becoming a more widely acknowledged idea that we all live in some life-place, and that maybe if we save those parts we can save the whole.

I want to tell a couple of stories from an urban context that point to ways we can fit into bioregions as a way to biosphere. Zeke the Sheik lived in Altadena, California. I learned about Zeke from a newspaper article that related how a man had been arrested in Altadena and charged with three civic crimes which were arson, violating the zoning laws, and operating a business without a license. This is what Zeke the Sheik did. He had built a compost pile that was over 25 feet tall in his backyard, and it worked so well that it broke into flames. The top of it caught on fire and necessitated the fire department to come and put it out. That was the arson charge. The business without a license was that he was distributing compost to his neighbors at an extremely small cost to cover his transportation expenses. He was giving out barrels of almost-free compost. He violated the zoning laws by having chickens on his place. He had simply decided to eat his own eggs. Altadena is a semi-suburban town so he was brought up on charges and treated as a criminal. Are you having the same thought I am, that he should have been appointed the minister of sustainability for Altadena instead of being arrested for doing these things?

In San Francisco currently there are explosions of feathers taking place outside of office building windows. Secretaries and CEO’s turn and look out the window at a burst of feathers. They might believe that they are in the midst of some supernatural phenomena. It’s actually the result of peregrine falcons diving down from the tops of office buildings and hunting pigeons. One of them has the poetically true name, Mutual Benefit Life Building. The birds are taking pigeons up to the rooftops and at the end of the day they fly back to where they roost under the bridge between San Francisco and Berkeley. The falcons have not only adapted to an urban environment, but they’re commuting to work!

I could really go on at length about these native hunting birds because they are so inspiring. They are doing us a service by symbolizing what we can be. We are animals too. And we are wild at heart. Our dreams are wild. Our bloodstream is wild. We shouldn’t solely cultivate postures and behaviors that are appropriate for operating machines, getting back aches and neck aches from driving cars or operating computers. We are human animals. The falcons are showing us that we can be wild in an urban environment with a high degree of elegance as well. Not wild like crazy, but the kind of wildness our predecessors possessed who made beautiful cave paintings in southern France thousands of years ago.

There are two directions that I think post-environmentalism should and will follow. The first is urban sustainability. To many people large cities are simply bad. New York and Los Angeles are not environments that they really enjoy. I also don’t generally like cities that are over about 100,000 in population, and there have been some cities that had populations of less than 50,000 and still produced great music and art. The bad news is that our present large cities can be awful environments, and the necessary news is that they are becoming the dominant habitat for our species. Our population is increasing at an extremely rapid rate and within a few years more than 50% of all homo sapiens on the planet will live in cities of 25,000 or more. The World Watch Institute estimates that this will probably occur at around 2010, but it may happen faster. There are some ridiculously overblown populations in cities today. Almost half the population of the entire nation of Mexico lives in Mexico City. China is planning to build 100 new cities of one million population or more in the next few decades. They’re moving the majority population of rural people off of the land in China to become urban dwellers.

Cities are not sustainable at present. They haven’t been sustainable historically and they’re not sustainable now. There are outstanding examples of great ruined cities. The Tigris- Euphrates Valley which is allegedly the cradle of human civilization is at this point incapable of supporting much more than goats. It’s been completely deforested, the rivers have been diverted, and the soil was ruined. Some ruined cities are still incredibly beautiful. One wonders why people would abandon Machu Pichu or Ankor Wat? They are like whole pieces of exquisite sculpture. The reason is that their inhabitants destroyed their local regional bases of support to fill basic human needs.

The only thing that keeps our present large metropolitan areas going is that they can still exploit their region or other regions for their continued support. For example, Los Angeles gets water from the Colorado River and northern California. Its liquid natural gas is from Indonesia. A large percentage of its labor comes from Mexico. Its electrical energy is derived from coal that comes from the Four Corners area of the Southwest. It is completely dependent, like a hospital patient. LA is alive because it is getting continuous transfusions from other places.

If we don’t attempt to transform these cities, we are performing a form of suicide for our species. I want you to answer the following questions as though you live in New York. Where does your water come from? A Manhattanite might say, “It comes from the faucet, stupid!” Where does energy come from? “The wall switch!” And food? “Everybody knows food comes from the store.” And garbage? “I’ve been thinking about garbage. Garbage goes out. There’s a parallel universe called out.” And the stuff in the toilet? “This is a real miracle of civilization. It disappears. Totally!” That is a suicidal view of the basic underlying resources that are essential for our lives.

The transformation of cities is perhaps the greatest challenge that I can imagine a person undertaking. The bigger a city gets the bigger this challenge is. How would NYC get its energy, food and water sustainably? How would it deal with its garbage and sewage sustainably? These are really formidable problems. Urban sustainability is an enormous transformative proposition and I encourage all of you to begin thinking of how this can be done. You may question the particulars of what is meant by “urban”, or question the term “sustainability”, but making cities harmonious with the regions where they exist and with the planetary biosphere is undeniably a major problem for our time and our species.

The other direction for post-environmentalism is the restoration of habitats and ecosystems. I just attended a memorial for David Brower. The older generation of conservationists was there to make tributes. Some of the ways they described being in nature were touching and beautiful, and also essentially different from what motivates people today. They were primarily Sierra Club hikers, backpackers and yodelers. These aren’t bad activities, of course, but they are different from what we think of now as the spirit of wilderness or wildness. We’re moving toward a different consideration of the natural world. Frankly, there isn’t a lot of it left. Have all of you seen the book from the Foundation for Deep Ecology titled “Clear Cut”? Please take a look at it. It’s the most brutally honest view of forests destroyed by logging that you could possibly imagine. It’s also a view that any one of you can have fairly easily just by taking a plane ride from San Francisco to Seattle, which I did this morning. You’ll fly over many of the clear cuts photographed for this book. In winter they’re particularly visible as checker board-like squares full of white snow that stand out from the uncut green trees around them. There is extremely little of the original primary forest left in North America.

We are even running out of water now. Naturally pure water is disappearing fast. In the American west, the biggest ecological question is becoming: where will sufficient water come from? We’re polluting water, diverting water, and consuming water to a degree that will soon outpace available supplies. A lack of potable water may be the biggest limiting factor on the quality and numbers of human lives everywhere on the planet in the future.

Environmentalism wasn’t really addressing the issue of “we are the human species sharing the biosphere together interdependently with other species and should have the long-range goal of doing so harmoniously.” The previous directions of environmentalism were mainly to stop polluting air and water, to protect human health, and to slow down the destruction of nature. This was essentially from the mental perspective of industrial society surrounding nature. Actually, nature surrounds industrial society. We’re in the biosphere, not in the Boeing aircraft factory parking lot. We’re not in a human created environment, we are animals in the wild biosphere.

Cities need to become more self-reliant. Suburban-type communities like Altadena, California need to develop a public presence or governmental presence about sustainability and restoring the ecosystems in that area. How do we sustain them? How do we restore the natural systems that have been destroyed in them?

First of all, we need to start seeing these sites for human inhabitation as existing in bioregions. What is a bioregion? This idea doesn’t come from pure natural science. Bioregionalism is a cultural idea. It’s an attempt to answer, “Who am I, where am I, and what am I going to do about it?” It’s a way for people to look at the place where they live in terms of fitting into natural characteristics.

As an introduction to this way of thinking, let me show a map (slide 1) of the continent of Australia that contains a few physiographic features. It shows wetness in green and dryness in brown, as areas of desert and vegetation. Answer this question: “Where do 85% of people in Australia live?” If you answered that they live in the green parts, you qualify as an instant bioregional expert! They live there because the average topsoil on this entire continent is only about two inches, and almost all of it is in the relatively small area where there is abundant rainfall and vegetation grows. This is also where the major cities are. People are conditioned by bioregional phenomena.

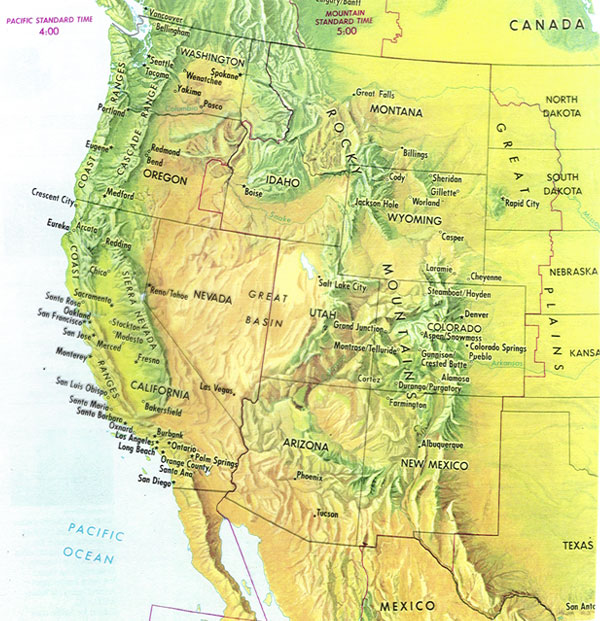

Next I want you see a physiographic map of the western U.S. (slide 2) and it shows two kinds of information. Not only wetness and dryness, but also the political boundaries of the area. Let me start with the political boundaries first because this is a really unfortunate situation. Here we have what might be the longest straight line on the planet, the main part of the border between the U.S. and Canada. It goes all the way from the Great Lakes to the Pacific Ocean. Look at this photograph of part of that line running across the Cascade Mountains at the border between the U.S. and Canada. Not only is it a line on a map, it’s a line on the ground that’s herbicided and defoliated every year by both countries for about a space of a hundred feet on each side. You can see the line of snow on the border running straight through a wilderness area, and it has identical natural systems on both sides. There’s no justification for making this line, unless you think that Mother Earth will forget who owns her and therefore needs to be branded.

Here are more straight lines between U.S. states. Montana has mostly straight borders. Wyoming is a complete square, one of the more vertical and least rectilinear places on the planet.

In more natural terms, it’s interesting that you can see on this map how storms coming in from the Pacific break on the coast, the Cascade Range, and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. That area is green which means its wet, and then there’s the brown, dry rain shadow on the other side in Nevada and the rest of the Great Basin. Then it gets green again where the Rocky Mountains are wetter. So we can see that there are large-scale different natural phenomenon here in the western part of the United States.

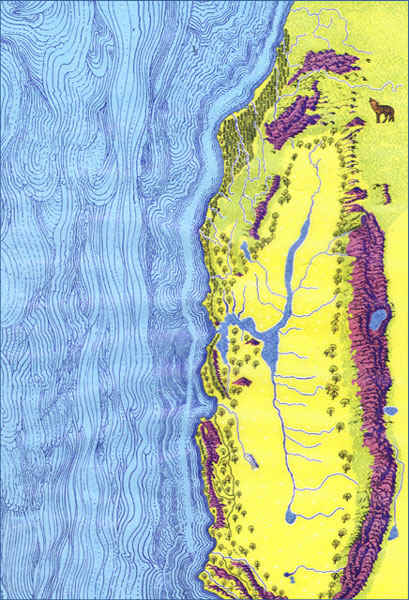

I want to show you an image that is a separate bioregion within this large area. The State of California was artificially patched together from several different natural life-places, but this is a bioregional map of Northern California (slide 3). It shows San Francisco but not the area around Los Angeles because that is in a different bioregion. Half of the map is ocean, because we saw that is where most of our weather comes from. That’s the source of San Francisco’s fog, from the California Current running offshore at around 50°F year round. The climate is winter-wet, summer-dry, or Mediterranean. It rains in the winter and never rains in the summer. The bioregion is within a mountainous bowl formed by the Sierra Nevada, the Coast Range, the Klamath-Siskiyous, and the Tehachapes. It’s an extremely large watershed. In the middle of it, two main rivers, Sacramento and San Joaquin.

In terms of vegetation, the totem species of this bioregion is the redwood tree. It doesn’t grow anywhere else on earth. Douglas fir forests are strung along mountains on both sides of the bowl, oak trees abound in the valley. To give an idea of the great diversity of vegetation, there are as many species of oaks in Northern California as there are species of trees in Alaska. The bioregion has been named Shasta for Mount Shasta at the northern end of the Central Valley.

These are the major characteristics of a bioregion; watershed, landform, native plants and animals, soils, climate, and an adaptive human relationship about living in that place.

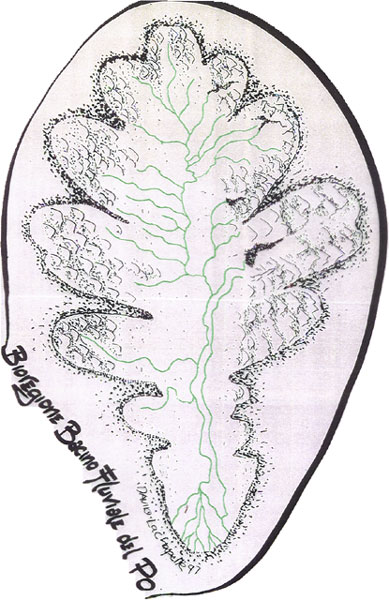

To reassure you that the map of Shasta Bioregion isn’t just a single isolated view of reality, here is an image of the watershed of the Po River in Italy (slide 4), which has a very active association of groups called the Italian Bioregional Network. At one end is the city of Milan in the Alps, and Venice is at the other end in the delta of the Po at the Adriatic Sea. The bioregional name that has been given to this area is “Bacino Fluviale del Fiume Po,” the Water Basin of the Po River. The map has been made in the shape of an oak leaf because the climax vegetation form in that area is an oak forest.

So, the idea of a bioregion is based on natural characteristics and natural science, but it is a cultural view that’s not only held by people in parts of North America, but also Europe. There are active bioregional groups in South America, Australia and Japan. Bioregionalism is becoming a popular movement that roughly follows the idea that people who live in a place have a certain inhabitory obligation to live in harmony with the natural systems that are there. We call this reinhabitation, becoming inhabitants again.

What are some of the things these groups do? They are really quite diverse. It might be a group of Catholic sisters living on a communal farm in New Jersey. Or tree sitters who are resisting logging in northern California. It might be a group of farmers in the Great Plains who want to find a way to stop destroying the soil and water resources of that area by finding human food and materials resources from native plants, rather than the present monoculture of grain crops such as wheat, corn, soybeans. There are actually several groups doing this including the Land Institute which has a basically bioregional perspective. Also an organization named the Kansas Area Watershed Council, or KAW, the sound a crow makes. There is a group in the Ozarks called the Ozarks Area Community Congress, or OACC after oak, the dominant tree form there. There are several bioregional groups in Mexico. The most inspiring one for me is near the town of Tepoztlan in Morelos where local people resisted a multinational globalist invasion by land developers to build a golf course resort using their water resources. They called their resistance “The Golf War”, and they were successful after five and a half years and a dozen people killed. They prosecuted the governor of the state on charges of bribery, and the new president of Mexico has given them back the rights to the water in a legal form so that they hopefully won’t have this problem again.

From a bioregional perspective, water is one of the first things to consider. How can we live with available water sources without diverting or destroying them?

Agriculture. What kind of agriculture is important to this life-place? The most appropriate form of agriculture for a bioregional context is “permaculture”. For example, you aren’t able to grow the same kinds of things with natural means in the Sonoran Desert Bioregion in Arizona as you could in Cascadia Bioregion around Seattle. Agriculture needs to be bioregionally reconfigured.

Energy. We can’t keep thinking that our future is going to be dependent on fossil fuels and nuclear power. We have to develop renewable energy sources. You can see right away that those are going to be bioregionally determined. For example, in Cascadia using mini-hydropower makes sense because there is abundant flowing and falling water there. But you wouldn’t think of using small-scale, local hydropower in the Sonoran Desert where there is little water. That’s a good place to be using direct solar energy instead.

We can’t think of sustainability in a jingoistic, economic determinist way. We have to think of it in terms of regional realities, and the grounding for that has to be in harmony with local natural systems as they occur where you live.

About borders of bioregions, these aren’t strict boundaries. They aren’t straight lines such as on the map I showed before. They are usually soft, and can be 50 miles wide. They could in some cases be as sharp as the crest of the Cascade Mountains where you can actually step over from from one bioregion to another, from the wet side of the mountains to the dry side. But in most places, the phasing between bioregions is more gradual.

The practice of living in a bioregion is proactive, and I think this is an important point for making an aside. Environmentalism had protest as it’s reigning activity. Most people have the view that environmentalism is somebody telling them, “No”. Urban sustainability, and restoring habitats and ecosystems, are positive activities. People can actually make their livings doing these things. Unfortunately it’s not a lot of people yet. However, at some point in the future when hopefully there will be more subsidization and more local community support for it, there will be a great many ways that people can support themselves in this way. At present, for most people, it’s mainly pursuit of a life-way. Most of the bioregionalists I know are following a path that leads towards bioregional connectedness and identity.

The implications for bioregionalism are numerous. Politically, governmental borders should follow natural watershed lines. In terms of education, school children would learn the bioregional realities of where they live. Isn’t it amazing that we don’t teach that in school? That we’ve gotten to this point in environmental awareness and ecological destruction, and we’re not teaching children the bioregional characteristics of where they live, or their connectedness with them, or the activities that are appropriate for living in a specific life-place? In terms of philosophy and literature there are obvious implications. Paintings can easily relate to the natural phenomena of the place where the artist lives, or poetry. Gary Snyder is a writer who will be known in the future for leading a transition for North American literature: from Europe to the Pacific Rim, and to life-places like his own Shasta Bioregion in northern California. Culture can go straight to wilderness for inspiration rather than just relying on industrial civilization.

How do you accomplish bioregionally based urban sustainability and ecosystem restoration? Even though I wrote a book titled “A Green City Program for the San Francisco Bay Area & Beyond,” I’ve been frustrated trying to do this where I live in San Francisco. Our mayor on Earth Day last year said that he was very concerned with the “gashouse effect”! He must have meant greenhouse effect, but no one corrected him and it shows that urban sustainability doesn’t have the highest political priority in our city. In fact, making cities compatible with bioregions is difficult to do anywhere.

I’ve been working in a city in Ecuador that suffered two major catastrophes in 1998. There was an El Niño during which it rained every day of the year and caused massive mudslides that wiped out whole barrios of the city, killing 16 people. The other disaster was a 7.2 Richter earthquake. The type of construction there is such that no building over two stories survived without severe damage. The people had to restore the buildings and infrastructure, and they decided to do that by becoming an ecological city. It was an attractive idea because they thought it would preserve some of the nearby surrounding wilderness. It might also attract eco-tourists for some new economic benefits. They asked various international groups for help, and a Japanese mangrove restoration organization named ACTMANG supported me to go down there. In no time at all I became absolutely intrigued because this is a place where you can do urban sustainability and ecosystem restoration at the same time.

Let me show you a bioregional view of the city of Bahía de Caráquez in coastal Ecuador. (slide 5) The “bahía” or bay is actually part of the estuary of the Rio Chone river where it flows into the Pacific Ocean. The hillsides are covered with dry neotropical forest, a more rare form than rain forest. The city starts on a sand spit at the mouth of the river and extends inland from that point to include various barrios. The ridge tops of hills tore away in mud slides during El Niño, and whole hillsides came down into the city as mud flows. The distances of fallen away soil were 20 to 40 feet. This event happened almost instantly and that’s how people were killed.

The bioregional characteristics of this place are vividly obvious. There is an island in Rio Chone visible from the city where at least six species of birds roost in incredible density. (slide 6) It is common to see several thousand birds there at any time.

This is photo of a boy standing in a boat in the river holding up a fish he’s just caught. (slide 7) The house behind him is made out of bamboo that’s been split and pounded out flat. Making a building like this doesn’t involve using money. The canoe is dug out from a tree which also doesn’t cost anything. Bait can be obtained by scooping out some shrimp. The fish can be eaten or sold in the market. Many people here don’t make much money and they can live at least partially from natural resources, parallel to the money economy.

This is the main market place where the boy might take the fish to sell. (slide 8) There are only a couple of cars in front because they aren’t the dominant form of transportation here. The most popular is bicycles, and for cargoes, tricycles outnumber trucks. “Triciclo” drivers are strong and incredibly imaginative. They seem able to carry anything on one of these things. I’ve seen up to five people at once, fifty liter water barrels, enough construction materials to build a room, even a coffin.

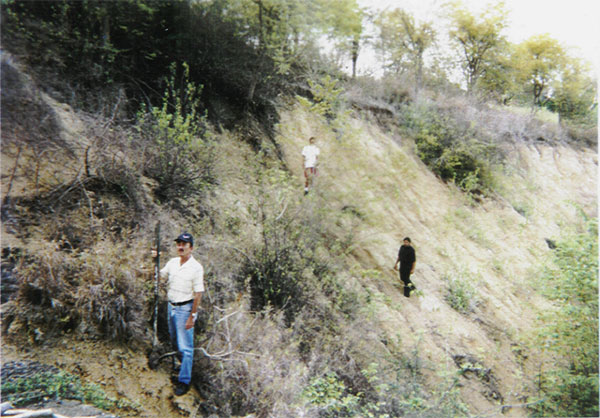

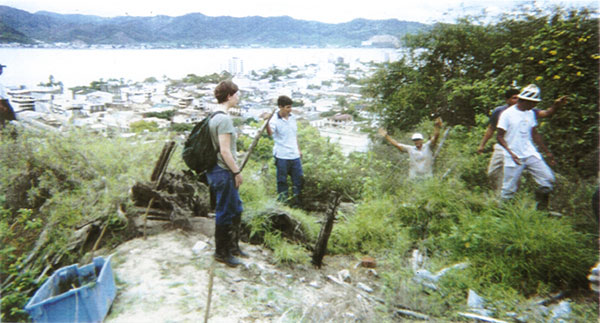

The naked sides of these hills are what the mudslides left behind. There used to be a road here but it was carried away. There is a man standing in the middle of the denuded hillside and the top of the hill is above his head. (slide 9 and slide 10) We saw this as an opportunity to revegetate with native plants to help prevent further erosion in the next El Niño, and also create an urban wild corridor park. Unfortunately, El Niños are becoming more frequent as part of global weather change. This has particular significance in Ecuador. If your house gets wiped out and you have to go live in a slum-like temporary dwelling, it can mean more than just inconvenience. Mosquitoes are everywhere in the rainy season. Around half of the children in temporary shelters have malaria.

Planet Drum Foundation decided to make a revegetation site where there was a mud slide close to the center of town, only two blocks from the main market. If we’re successful, it will stop erosion and also establish the restoration of natural systems as a part of making an ecological city. (slides 11 and 12)

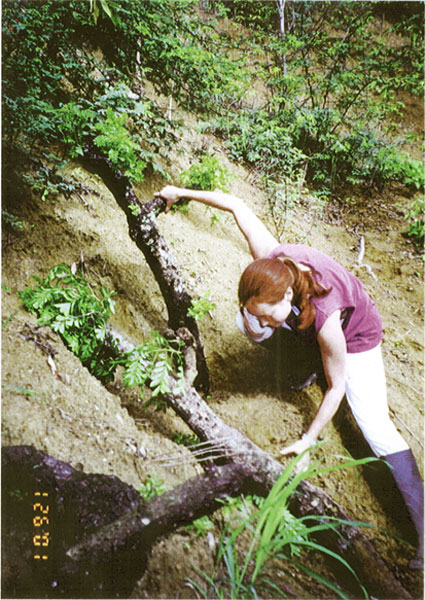

Within six months we were getting good results with some grass growing about four feet tall, called locally paja macho, “tough grass”. Grass allows the rain to run off instead of soaking in to cause slides. We also pushed in stakes of native plants. They will become trees with roots that will hold the soil when it does get somewhat saturated. Perhaps one quarter of the arboral species in a dry neotropical forest will grow from a cut branch that is simply stuck in the ground.

You can see this was cut and sprouts of leaves are just beginning to come out. (slide 13) When we were about half way through with this project we put up this sign to make bioregional language public. “The area in front of you from here to barrio San Roque has been revegetated with native plants of the bioregion of the Rio Chone estuary. They were planted to help prevent future erosion and to create a wild corridor of the neotropical dry forest.” We don’t have any signs like this in North America yet. I’m really proud that there is at least one somewhere.

There are other ecosystem restoration projects in Bahía, and this is a photo of replanting mangroves. (slide 14) Seed pods are being stuck in the mud between two mangrove islands. The aim is to restore the estuarian mangrove forests that were cut down to create shrimp farms. In the recent past, hundreds of shrimp farms were made in this way, with much of the shrimp coming to the United States.

This sign at the central market place says “Bahía’s people recycle garbage.” It refers to sorting out organic wastes that are then used to make garden compost. Here is another sign on a building that says “arte papel”, or art paper. Economic reality dictates that paper should be recycled because it can be useful. In this women’s collective, art paper is made out of office refuse and then decorated with parts of flowers and plants to be sold as special stationery. Planet Drum Foundation donated part of its office space to the dozen women who are now making part of their living from this activity. (Click here to see examples of Arte Papel.)

This (slide 15) is an enterprising “triciclero” who decorated his tricycle with a sign for visitors, “Welcome to Bahía, the Ecocity”. It also celebrates non-fossil fuel transportation.

Here is a parade of the Ecology Club, about 150 children between eight and sixteen years old. (slide 16) They’re marching on the first anniversary of Bahía’s eco-city declaration.

Bahía still has major social problems. The national economy is in shambles and banks fail regularly, unemployment is high, incomes are low, education is lacking. Ecuador had a huge social transformation in 1999: an Indian-led rebellion. Many South American places have large indigenous populations. In Ecuador it’s 40% of the people in the whole country, and 75-80% in the mountains. They brought down the government and have created a separate, inter-tribal, extra-governmental organization to represent social grievances. One month after the government fell, people began rioting in the area of Bahía that was built as temporary housing for victims of mud slides and the earthquake that has open sewers and malaria. In this photo they’re burning tires to block the main highway, protesting malaria and the fact that the roads were impassible during the rainy season. They effectively stopped all traffic until the “municipalidad” sent out trucks to fill in malaria pools and smooth down the roads.

(click here for additional photos of ecological activities in Bahía de Caraquez)

It’s inspiring for me to be able to work in Bahía because the people, mayor and city council are behind making an ecological city. The main limiting factors there are money and skill. Ecuador is extremely poor, the average pay for labor in the field is $6 a day. In spite of the economic obstacles, the municipal sewer system is being studied for transformation into a biological, non-chemical type, using an artificial wetlands primary receiver of sewage that would be planted with native plants and create a habitat for native animals. The garbage collection service for the city can eventually be turned into a recycling company. We have just finished a project in the poorest barrio to separate garbage so that organic material can be used to make compost for growing fruit trees beside homes there. In January 2002, I’m going to bring a renewable energy specialist to help decide which form of renewable energy would be best to use there in the long term. It won’t make sense if we come up with some elaborate thing that nobody can afford or nobody wants to use, so it has to be vernacular and as usual we’ll be getting most of our ideas from the local people.

When I’m asked what should we do first or what do I think is the most important thing to do, I always say ecological education. Bioregional ecological education. Because sixteen year old high school students are going to be twenty-one in five years, and that’s an age (especially in South America) when many are already married with children and probably have a career path laid out. Those are the people who are going to make an ecological city.

Isn’t it remarkable that the idea of an ecological small-sized city is coming out of the undeveloped world in South America? This model is certainly going to make sense in the so-called Third World, much of Asia, Africa, parts of Europe, and the rest of South America. Since a lot of the early work of how to put these things together is being done there, Bahía de Caráquez represents a kind of teaching institution for visitors and students to see how the transformation into an ecological city can be done. The implications of this kind of work in Bahía and other places can actually flow back to the developed world as well.

As an appeal to your imagination, I’m going to close with a poem by Lew Welch.

Step out onto the Planet.

Draw a circle 100 feet round.

Inside the circle are 300 things

nobody understands and,

maybe, nobody’s ever seen.

How many can you find?

Questions and Answers

(Question from audience)

Berg:

The questioner asked me to talk about Missoula somewhat. I’m ill-prepared to do that since I don’t live here, and as a bioregionalist I believe the people living in a place ought to be the ones who state the problems and seek out solutions. Somebody told me that the population of this area has increased by 44% in Ravalli County, in how short a time? Within 10 years. It strikes me that this is a serious problem in terms of reinhabiting this place if it means increasing the number of people but they are doing the same things that have been done before. Several counties in northern California now distribute a booklet called Watershed Owner’s Manual. A watershed owner is anyone who lives in the county. The manual is a description of how the watershed works, what pollution occurs, where it comes from, how to recycle, and other aspects related to living sustainably. One of the things you could have is a Bitterroot Valley Watershed Owner’s Manual, that said, “Welcome to the Bitterroot Valley and this is how you live here.” There’s something like this in Tuscon, Arizona. There has been a Sunbelt invasion there that increased the city population more than 200% in the last 10 years. So in Tuscon, which is in the Sonoran Desert, people are moving in from Chicago who want to have English lawns around their houses. There isn’t enough water for that. The Tuscon Chamber of Commerce brought out a book that said, “You live in the Sonoran Desert, here are the plants that grow here – jojoba, saguaro cactus, mesquite. Love these plants, put them in your front yard and don’t make a lawn, leave it sand. That’s the way we like it in Tucson.” This is necessary because their water supply is from a fossil aquifer, it’s going to run out.

We have to begin practicing water reuse, especially west of the Mississippi. You have to do it here in Missoula. An example of water reuse would be to take the water from your shower and use it again to flush the toilet. For some people this seems to be unthinkable. They would rather use pure Rocky Mountain spring water to flush. They would feel unclean if their feces were surrounded by anything as supposedly dirty as the water from the shower. But we could cut water use by as much as 50%. I have been in homes where this was actually done without any mechanism, but a small pump and a filter with a second set of pipes would be all that is necessary anywhere.

There are many examples of redesign that make a lot of sense. Here’s a simple example. The Japanese have sliding doors in the interior of their homes instead of doors that swing open. Every door that swings open requires an empty arc of free space for the door to move. Japanese sliding doors eliminate that space. When they construct a building they make floor space smaller with just that one technique. If we are talking about living more sustainably in dense urban circumstances, those are the kinds of things we have to do. The Japanese got into that a long time ago, because they had a lot of people living in some very small areas. There are some wonderful traditional Japanese methods for saving heat, like sitting around a central small heater in the living room during wintertime with a blanket around everybody.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

The questioner brought up the fact that we are currently having an energy crisis in California and asked what effect that has. These are the kind of opportunities we should look for. I don’t see this as a single energy crisis, but as a clear indication of what the future is bringing in general. It is hitting energy use right now in California, it is going to hit water, it is eventually going to hit food throughout the Northern Temperate Zone. It is really important to see that all of these things – water, energy, agriculture, materials, building materials, and also education, culture – are the main areas that we have to stress for a bioregional sense of sustainability and locatedness. We are going to use this as an opportunity, we are going to say that we can’t rely on fossil fuels, and we have to have a more reliable public source of energy.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

She brought up the issue of water diversion in the Phoenix, Arizona area and how to handle limited resources in a local way. Often, practical issues don’t actually begin with how cheap one thing is over the other or whether or not it’s easier to walk than to ride in your car. They often originate with larger ideas. One of the large ideas with this issue is what is the basis for mutualism within a community? What is going to be our basis for mutualism? The people that dreamed up eighteenth century democracy didn’t know what democracy was. The French Revolution guys running around yelling liberty and equality didn’t know what liberty and equality were. They just imagined what those things would be like. In a similar way, we don’t have to know everything about interdependence, living harmoniously in a bioregion, to describe it as a direction. We can sense that it is better than what we are doing now. In terms of cities, we are in a suicidal situation. In human species terms, I believe that we are losing our wildness at the same time that we are destroying wilderness. One of the reasons for achieving urban sustainability, by the way, is to maintain wilderness. So, I think we have to start lending our voices to the idea that there are higher purposes. Today, in a city council meeting you can stand up and say, “Wait a minute, we have one person one vote. We are supposed to have a democracy here. I have freedom of speech.” We need to start standing up and saying we live in a bioregion together and should be thinking of bioregional sustainability, making cities harmonious and restoring ecosystems as a basic fundamental activity of government. Then people will say that it’s most important to consider that the river that goes through Phoenix, Arizona is completely diverted before it gets to the Gulf of California. We have to begin expressing this kind of perspective, raising consciousness about bioregional sustainability and teaching it to children.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

Her question is, how does one get around to solving the serious ecological problems of larger cities, as opposed to smaller ones or in South America? You are absolutely right, the level of disinhabitation of the urban population in North America is profound. City people often have little idea of where they are or even where their resources are coming from, and the big city environment is a hurtful environment. It took me two years of living in New York to realize that after two years most outsiders leave. Naively, I imagined that people moved to New York to live there, but if they secure an economic base of some kind and continue working there, it’s such a harsh environment that they usually go to live in Connecticut or even northern Pennsylvania.

The reason why World Watch Institute established a population of twenty five thousand people to define a city, which is a small number in our perception, is because that level of population is quite large in a great part of the world; South America, Africa, and Asia. That’s where only about thirty percent of the people live in urban environments and seventy percent still live on the land. This is changing very quickly, but the reason why you can’t judge by the United States where seventy five percent of the people live in urban areas is because of Africa, South America and Asia. World Watch felt that twenty-five thousand was about the number of people who could no longer self-reliantly support themselves. In other words, they couldn’t farm to grow their own food. If you look at the whole planet this is about the size of a lot of places. There are more urban communities of up to one hundred thousand than there are over one hundred thousand. The number of communities is greater, if not the quantity of people living in each one. So it is very important that twenty-five to one hundred thousand range population urban areas are made ecological. It is especially important in the so-called developing world where people are coming out of agricultural backgrounds and entering urban environments. You may disagree with this personally, but it is a main push in the Third World.

For cities of over one hundred thousand, it’s a case of not what you do but the way what you do it. We don’t know what the human carrying capacity is for a bioregion, no studies have been done. We don’t know which adaptive techniques would yield the suitable number of people. How many people can live in a city? I previously gave the example of Japanese doors to show how a simple thing can have a large impact. What would happen if we began growing vegetables on rooftops of city buildings? In India it is not uncommon to find vegetables such as fava beans growing on top of house roofs. How about alternative energy installations? How many types could be used? In what circumstances? How much of the energy consumed in a city could be provided by renewable energy through direct solar or windmills or whatever? Water reuse, if you reuse fifty percent of the water how many people can live there? To me these are open questions even though I see the prospect as daunting. I was just in New York to make a presentation at the International Forum on Globalization conference in the heart of Manhattan. Somebody asked, can New York ever be sustainable? It was extraordinary to even consider it. It’s like a Grand Canyon of impossibility there. What went through my mind was, well, how could we know this? How do we know what we can do unless we start doing it? For example, when Berkeley, California, proposed a law that fifty percent of the household waste should be recycled, the opposition said fifty percent was clearly impossible. Today it’s over eighty percent without really trying that hard. I don’t know about the biggest cities, but transforming Missoula would be a good place to start.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

Her question is, how can you involve the resident population of the mainly rural west or mainly rural areas of United States in the kind of environmental activity that has been accepted by liberal populations in larger urban centers? There is a program that the US Bureau of Land Management has been trying out in northern California whereby logging plans have to be approved by a three-part group that includes BLM, logging companies, and local residents. In the areas where they are trying this out, the resident populations happen to be largely conservation oriented. They see this as an opportunity to positively affect logging plans so that clear cutting will stop and that the borders of cutting plans are honored. Traditionally, lumber companies are sloppy about the edges of places and may go over them by fifty yards on each side if they can get away with it. So, the plans are being reviewed and approved or vetoed by residents. That is a good model. If you can effectively organize the conservation-oriented population in an area to take part in that kind of activity, attend public hearings and push for public approval, this sort of model can only be beneficial.

Rural demographics are changing very fast. The reason why there is so much opposition to logging in northern California isn’t because people who used to cut them suddenly fell in love with redwood trees. It’s because back-to-the-landers and stay-at-home workers with lap-top computers moved into former logger populated counties. When they saw a redwood tree fall outside the window they jumped on the computer and started bitching about it. When Freeman House is here next week ask him to describe the rural community that he lives in and how it operates and you’ll see an example where the demographics have been completely reversed. There is more reason to trust the community to make ecologically sound decisions than there was previously.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

You know, I don’t think they would understand ecosystem restoration in Chicago now. It would be nice to show them somebody growing native plants in a vacant lot, but it is not going to really have enough impact for them to start reusing water inside condominiums. For this to occur, there has to be a bioregional context. People need to think of living in a city sustainably so that they can preserve and maintain the basis of life.

There are three goals for bioregionalists: restore and maintain natural systems, find sustainable ways to fill basic human needs of energy, food, water, etc., and support the work of reinhabitation.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

The question is, how to balance or whether to even attempt to balance methods that might be not agreeable from an ecological perspective that are used in the name of improving some sort of natural features such as removing noxious weeds by using pesticides. I am an extreme idealist. I believe that we have to begin thinking of ourselves as a human species and that we have to begin thinking that we are interdependent with the other forms of life, and that we live in a bioregion and that gives us a certain sense of obligation and responsibility.

However, I’m working in Ecuador where things need to be extremely practical. Somebody there may say, why don’t we poison the hell out of those weed plants over there? I’ll reply that poison costs money and there might be a natural way to do it, why don’t we do that instead? You go to a meeting with ideals of living interdependently in a bioregion and that you have to be thinking in mutualistic ways, but phrase them in practical terms to get results.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

Why is environmental education so important? Well, if they learn ecology from the sixth grade on, children would come home telling their parents that this is the way they want it to be. There was a wonderful article in the New York Times awhile back. It was a sardonic story by a woman with a title something like, “Thank God my daughter is going away to summer camp”. She wrote that her fourteen year old was giving her a badly needed break. While she was gone, it would be possible to smoke in the apartment without going outside. The mother would be able to just throw things into the garbage without recycling. She would buy whatever she wanted at the supermarket without reading labels for healthy ingredients, and she wasn’t going to have to talk about the death of whales all day!

Kids are doing it in Ecuador, coming home and telling about ecological activities that they did during the day when we take them on field trips. Sometimes the parents report back to us that they used to do the same things themselves, eat this or that wild food and so forth. It’s a beautiful thing to see a child describing something to the parent that the parent remembers in some way and feels strongly about as well. It is a sacred circle.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

A good argument is the difference between price and cost. The gain that you get temporarily may not be worth the loss that you suffer in the long run. Where I have been working in Ecuador, a neighboring city council asked what they should do with the remaining dry tropical forests that surrounded the city. Should it be cut down? They said there was money to be made that way. I said, if you don’t cut it down and wait five years people will come and pay much more money just to look at it. The dry tropical forest is rarer than rainforests, it has unique and spectacular species.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

The question is, if China is urbanizing so fast, it is going to be a biospheric debacle, and isn’t it a great opportunity to start using some of the ideas that have been discussed tonight? The current primary philosophy in China is materialistic and oriented toward industrial progress. The Three Gorges Dam project is a good place to do an action. It is already half built and if it is finished it is going to flood an incredibly large area of the Yangtze River Valley, drowning hundreds of towns and cities and displacing millions of people. It will also destroy much of the cultural heritage of southern China. It’s supposed aim is to enable China to be able to make a materialistic jump forward.

Any action in opposition would have to be with the involvement of local people.

I wouldn’t be in Ecuador unless the city there had voted to become ecological. I am actually the volunteer consultant to the mayor of this city now. It takes the involvement of local people.

Gratefully, there are people in China that are talking about ecological cities, in the Academy of Sciences in Beijing. There are organizations in Hong Kong headed by enlightened environmental people.

(Question from audience)

Berg:

The statement is that tourism is already the number two industry in Montana and that a form of eco-tourism would be a way to make a transformation towards sustainability. A group in England put out a list that said, what is the difference between tourism and eco-tourism? There were a dozen or so points. The first for regular tourism was, travel to foreign lands in a fossil fuel consuming means of transportation. It was the same for eco-tourism as well. The second was, stay in hotels where local people wait on you. That was the same for both kinds of tourism. All the way down the list they were exactly the same until the very last one for tourism which said, take photos of people and monuments. For eco-tourism it said, take photos of plants and animals. Putting “eco” in front of a word doesn’t necessarily change anything, there has to be a bigger difference than that.