Three Dispatches are below from Japan, China and Mongolia

(most photos by Judy Goldhaft, some by Peter Berg and some by Kimiharu To)

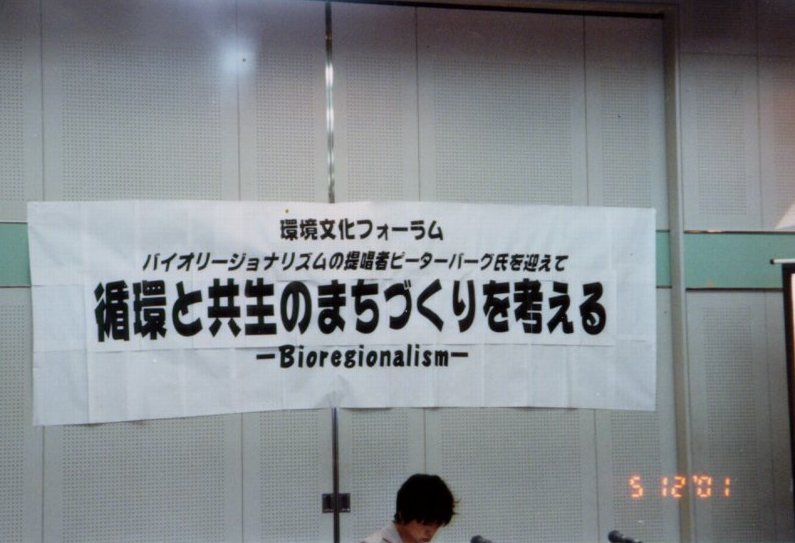

Bioregionalism Finds Eager Audiences In Japan

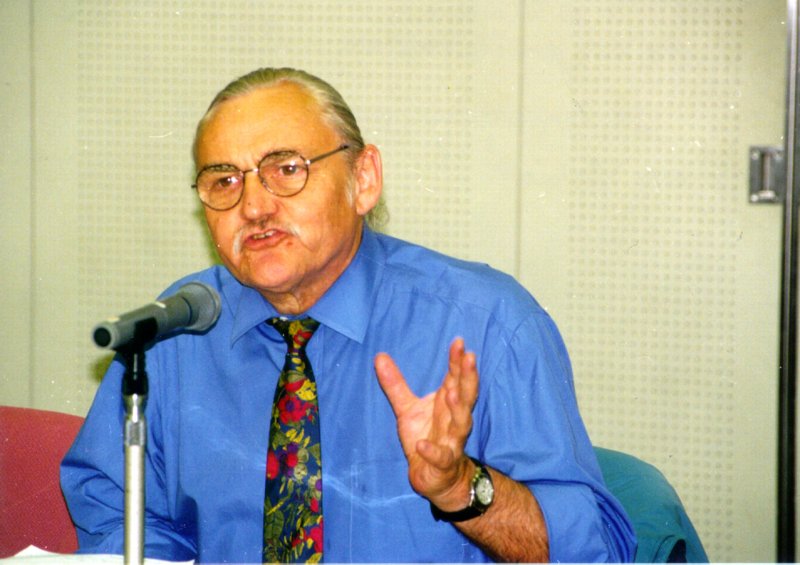

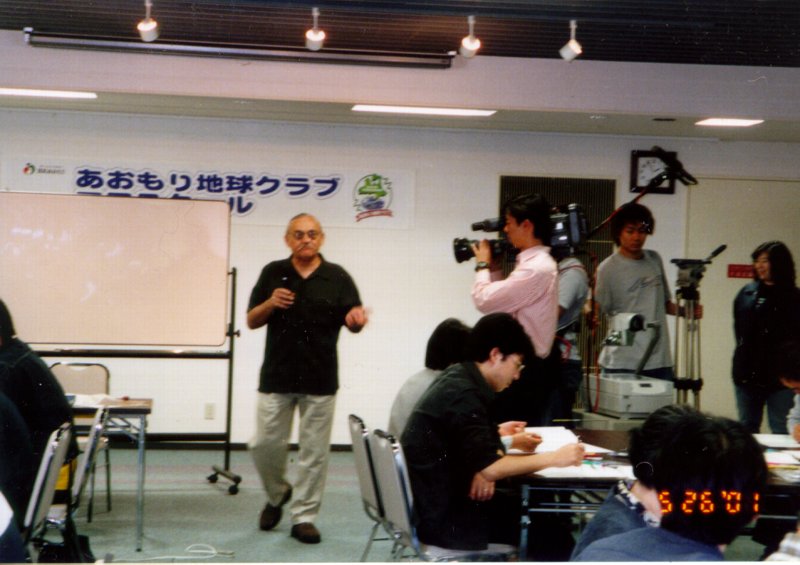

Planet Drum Foundation concluded a three week, five city tour of Japan on May 30th titled “Bioregionalism: Proactive Approaches to Sharing the Earth.” Peter Berg and Judy Goldhaft presented over a dozen talks, map-making workshops, and performances of Water Web in Osaka, Kyoto, Yokohama, Tokyo, and Aomori to crowds as large as 700 as well as small community groups.

College stops included Kyoto Seika, Meiji Gakuin, Aoyama Gakuin, Tokyo University, and Aomori University. Bioregional ideas have been accepted at surprisingly high levels in this country. Local government officials attended presentations in sub-tropical Osaka and two community workshops in far northern Aomori (where a local television station will broadcast extensive coverage). The central Japanese government environment agency is preparing a “white paper” on bioregionalism. Global Environmental Culture, a non-profit organization in Osaka, has published a book entitled “Bioregionalism” with essays by Peter Berg, Yuichi Inouye and Kimiharu To, and notable Tokyo magazines BioCity and Treeshade will publish interviews with Berg.

Most interesting to Planet Drummers was the development of watershed networking by local groups that is occurring in places as different as metropolitan Tokyo and Aomori Prefecture’s outlying small towns. Independent organizations are springing up to oppose dams, release rivers and streams from their cement prisons, and restore wild habitat. Awareness of the need for urban sustainability is rising with renewable energy posed as an alternative to nuclear power, “zero” garbage policies to benefit recycling, and bicycles to reduce both global warming and automobile traffic.

China’s Epic Conflict of Capacities

A regrettably familiar scenario is playing out on an ominous scale in China. It is a struggle between frenzied industrial capacity building, and the ecological carrying capacity that is necessary to support a future society. To dismiss the significance of this nation’s present conflict by saying that the same thing is happening everywhere would be likening a candle flame to a forest fire.

China has achieved an extremely large amount of industrialization in just fifty years. It isn’t necessary to quote statistics. Look in your clothes closet, investigate the hidden components in electronic appliances, or just empty your pockets and most likely some Chinese manufactured products will appear. They are everywhere.

The cost of this momentous surge has been enormous environmental damage at home. Boats leaving Shanghai’s city center dock to begin a trip up the Yangtze River are shrouded in eye-burning, throat-scratching, nose-stuffing smog. The only water actually visible is directly beneath the ship’s rail. The striking new multistory needle-shaped communications building that pierces a large shining sphere midway to the top dubbed “The Pearl of the Orient” lying just across the river in Pudong can barely be seen through the haze blanket.

Surely the air must clear up further down the river. But it doesn’t. All afternoon, steadily through the night, and through the next day and night, a gray curtain shrouds unbroken shorelines of smudged smokestacks, noisy power plants, rusty container freight booms, drain pipes spewing discolored liquid, squat factories, coal piles, and grimy rail yards. For more than a hundred miles the principal variation in air pollution from one of China’s largest industrial cities is its odor. There are distinct bands of stench that reflect burnt cardboard, coal smoke, braised metal, wood smoke, diesel fuel, or baked minerals.

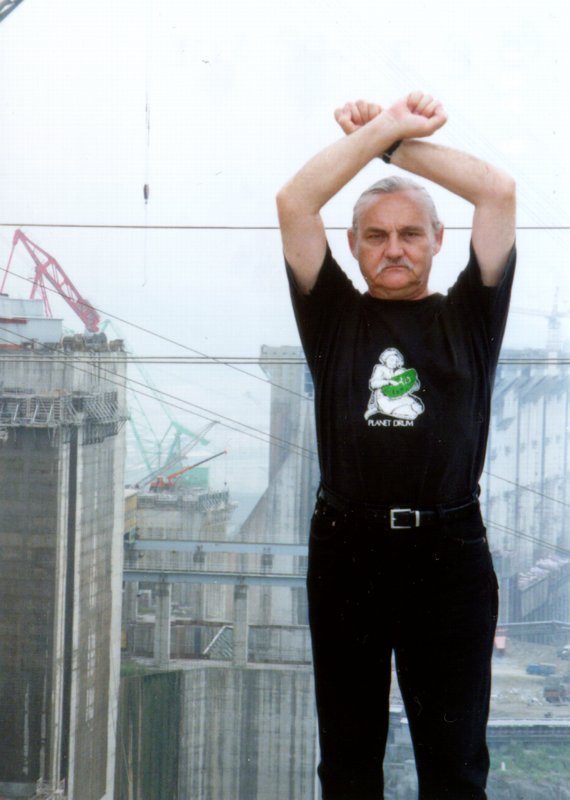

Although it is poisonous to life forms in general and especially injurious for human beings, air pollution as bad as this can eventually be reduced or practically eliminated if there is a will to do so. Unfortunately, further travel several hundred more miles up the Yangtze provides overwhelming evidence that China is following a completely opposite path. The grotesque Three Gorges Dam Project (3GDP) when it is initially completed in 2003 will throttle the river for over a thousand miles upstream and drown an inimitable part of Chinese cultural history along with a long-recognized part of the world’s natural heritage. The renowned and inspiring canyons of Three Gorges will be submerged by a wall-to-wall lake. Imagine turning the Grand Canyon into a landfill and topping it off with garbage. It is an equivalent loss, and the ecological impact will be even greater.

The 3GDP is a guiding symbol for what some feel will be the upcoming Chinese Century. “The fight of man with the [sic] nature for water resources” proclaims the inscription on a new monument above the dam construction site. It could just as well read “for everything.” The 21st Century will be a head-whipping era of accelerated urbanization in previously countryside-based China. Erection of new buildings is so feverish that no daytime cityscape is without the sight of several construction cranes. A dozen could be spotted in one quick glance even through the polluted air of Shanghai. Night time city views are never without dozens of small brilliant white beads from welding torches pricking the darkness.

There are dreary large black and white signs everywhere along the Yangtze banks proclaiming “135 meters” (for the reservoir’s depth in 2003) or “175 meters” (for the ultimate drowning in 2009). If the same brutal honesty prevailed in cities, there would be billboards proclaiming “135 million tons of garbage,” and “175 thousand pounds of air and water pollution.” Much of the rural population is slated to be moved off of the land (where more than half now live) to cram new buildings by the hundreds of millions. If this grim fantasy is realized, there should also be billboards listing dried up rivers, mowed down forests, ruined farm land, and sewage tainted seas (80% of China’s human waste is dumped into rivers and ocean bays).

This isn’t solely an outsider’s view. Resident critics bravely express similar and even more fatalistic outcomes. A particularly direct comment was, “China is like the Titanic. The current regime believes it is invulnerable and is about to hit an iceberg.” What will be the first cracking point? Ecologically informed urban observers point to strains on water supplies. Beijing’s rivers are already exhausted from a five to ten times jump in population (depending on how it’s counted) and a huge increase in industry over the last half-century. Drinkable water is sharply limited nation-wide and can only become more scarce. Lack of water is a planet-wide problem that may be felt most deeply here.

The 3GDP’s mission is to control flooding on the Yangtze, provide irrigation, and supply one-tenth of the total electrical power for China’s one and a quarter billion people. The largest dam ever built also has the greatest potential for problems: unprecedented water pressure from the world’s most vast reservoir, severe silt build-up from the perpetually brown Yangtze, and vulnerability to geological events. There is a sharp division of engineering opinions about the dam and ensuing hydrological phenomena. Catastrophic failure shouldn’t be ruled out. Even without it, the damage that will eventually be done by uprooting over a million people and flooding their cities and farms, submerging nine-tenths of the known ancient artifacts of the Yangtze Valley, and many other negative repercussions of 3GDP can stir fateful doubts about the government.

Is there any possibility for a positive outcome? The present regime deems itself “communism with Chinese characteristics.” One Chinese characteristic is to believe that rulers prevail through the Mandate of Heaven, which is unsuspectingly taken away from or bestowed on different groups. The turnover is usually preceded by a natural disaster such as famines or floods. The massive amount of overbuilding and technological/industrial capacity building currently underway symbolized by Three Gorges Dam may inadvertently cause such a calamity. Suppose people begin to feel that the Mandate of Heaven has been withdrawn from the Red Dynasty, and it no longer balances the needs of The Middle Kingdom. The debts to ecological capacity must ultimately be met, and may come due faster than we could hope.

Big Horizon Mongolia

We were feeling exalted.

Enkhtuvshin had spotted an ovoo, a conical pile of stones created by passersby who add one on each turn walking around the circle at the base and praying. They are usually sited at some powerful natural spot and this was the exact top of a ridge where large valleys could be seen on both sides. He poured a little vodka into a cup, said a lamaist/shamanist prayer, and sprinkled it on the heap. Then Jarga, Judy, he and I each drank a full cup of vodka, picked up three stones, and separately circled the pile three times intent on our own thoughts. It was a venerable ovoo, at least ten feet high with sticks inserted at the top that pointed upward another few feet like teepee poles with slender blue silk banners streaming in the wind. The outside of the pile included a dozen upright vodka and beer bottles, a pair of crutches, some empty food tins, and other personal offerings. My imagination cut through to the center of the pile to find more ancient artifacts: bells, beads, pieces of clothing, leather flasks…. We had more vodka. I thought of all the isolated travelers who had passed through with this monument as their point of intersection and companionship with other people. I raised my head and sang some of the words of Jim Koller’s poem “Wind: fragments for a beginning” to Michael Tierra’s melody.

Enkhtuvshin resumed driving and laughingly recalled, “Some Russians once asked me during a ride ‘Where is the next ovoo?’ They were hoping for another drink.” Toward the horizon we saw the forms of horses running on the hillside. It was the encampment of a herding family catching yearlings to add to a string of about a dozen. Two bare-chested riders with lassos at the end of poles chased a particularly elusive white and brown horse while a father, mother, son, and daughters sat on the grass around a sacrificial tray of cookies and candies. They bowed and voiced agreement while a lamaist priest-shaman read sutras.

We stopped and still carrying the comradery of the ovoo, walked toward them slowly and respectfully. The father welcomed us to sit down, told us it was White Dog Day and auspicious for catching horses, and immediately offered mare’s milk tea. When the priest stopped he took a snuff bottle from inside a worn jacket and offered a sniff of the spicy-smelling contents.

On journeys I carry candies for children and tossed one across the small circle for the boy. Jarga grabbed my arm forcefully, and said in a low but urgent tone, “Don’t ever do that again! Do you think he’s a dog? You only throw things to dogs. And never give anything with your left hand.” I was grateful to get the lesson at the beginning of our visit to Mongolia. Otherwise, it was a pleasant, semi-formal meeting with conversation ranging from the number of horses to the recent change of regimes from communist to democratic (although the communists actually won the last election). After chasing it for most of our visit, the oldest son finally caught the elusive horse, and grabbing its mane jumped on for a first ride. He was thrown within seconds, but after punching the small horse hard in the ribs, jumped on again and rode away. We added some sausage, pickled vegetables and beer to their lunch of sheep cheese, bread and vodka. After an hour the father said it was time to go and kissed me on one cheek. “The other cheek is for when you return. But don’t look for us here, we’ll probably be grazing up on the mountainside.”

We left and began driving toward the horizon again. There is a sense of undoubted freedom and self-confidence about seeing the horizon miles away on all sides. Things take form at the edge of vision and come toward you at the same time as you advance closer to them. Everyone is on the same ground. The horizon is more than the edge of a bowl. It is the slit of the world’s eyelids. When a figure appears between land and sky, the slit opens and you focus on what can seem to be the whole planet. The horizon persists everywhere in Mongolia. The capital city of Ulan Bator presides over a nation as large as California and contains nearly half of the country’s population of just over two million, but it is spacious with low buildings and open areas between them. With a national park actually inside the city limits, the horizon can still be seen in many parts of Ulan Bator by simply standing on the sidewalk.

Reader Interactions