Natural places are alike in that they have similar basic elements. They are conditioned by climate and weather, shaped by land forms and water catchement basins, possess soils and other geological characteristics, host native plants and animals, and have human populations with cultures that adapt to these natural features. The combination of these elements is a bioregional template.

What makes places different from each other are the specific details. There can be polar snow or equatorial sun, roaring rivers or still marshes, boulders or mud, palm trees and elephants or redwood trees and bears, fur clad Inuits in the Arctic Circle or naked Jivaros in the Amazon forest. All places have their own resonance that derives from these particular ingredients. This resonance provides an experience that only occurs in that particular locale, and it is perceptible to our senses in innumerable direct and indirect ways: distinct bird calls, the feel of mist on the face, or the rub of stones against shoe bottoms.

Undoubtedly the strongest perception is the way a place looks. Its appearance to our eyes creates a more complex sensory impression because there are so many visual levels. Each aspect has its own individual appearance and at the same time blends with the other parts. The shape of rocks has a particular relationship to the forms of native trees. Whitecaps appear on rivers in steep mountains but not with the calm snakelike movement of streams across flat plains. Light and shadow also shift dramatically according to the position of the sun at different times of day. The change of seasons can reorder everything, filling fields with the flash of flowers in spring and repainting green trees yellow and red in fall.

Hiroshi Yoshida avidly sought the resonance of different places from California to India as a foundation for his shin hanga woodblock prints. He soaked up each bioregional essence and distilled it into portraits that were as unique as the places themselves.

“Grand Canyon” shows the utter dryness of the desert that surrounds an astounding natural phenomenon. Instead of staring down into the deep gorge of the river that made it, he looks across the top of the canyon to show layered forms that were carved out by the water. The colors are faded by intense sunlight but still contrast with each other enough to show the huge masses of stone that were effected. The lack of people and trees isolates and heightens the perception of this single powerful force of nature.

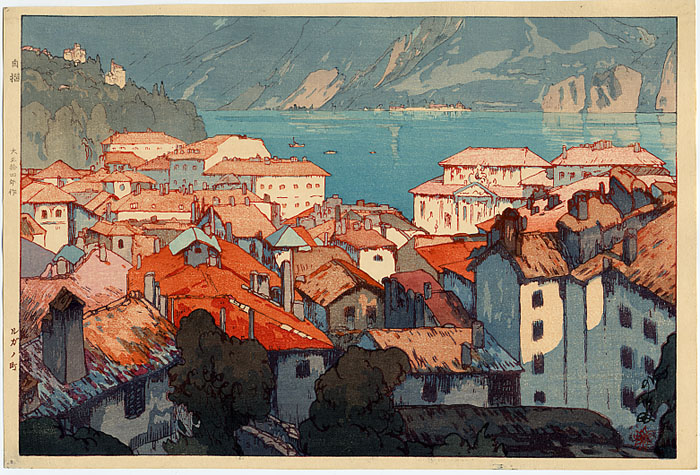

On the other hand, “Lugano” puts the works of humans prominently in the foreground. There is an ample array of Alps Mountains bioregional elements from calm Lake Lugano in bright sunlight to steep mountainsides and cliffs with only a trace of vegetation. However, Yoshida underscores the beautiful adaptive culture of houses made from native materials arranged in a descending pattern to fit the slope of the land.

The creative milieu preceding Hiroshi Yoshida was a unique crosscurrent of Eastern and Western influences. Woodblock printing had reached a zenith with Edo era ukiyo-e depictions by Hokusai and Hiroshige. When examples of this style reached Europe they had a significant influence on Impressionist works by artists such as Van Gogh (who actually copied a Hiroshige poster), Gaugin and Lautrec. Within a few years Impressionism came to Japan where the forms and colors of Cezanne and Monet began to seep into the new shin hanga woodblock print style.

Yoshida’s “The Sphinx” exhibits this influence clearly. With only a few large blocks of juxtaposed light and dark color on the bottom half of the face, he impressionistically indicates the roundness of the Pharoah’s cheek without extensive detail, just as Cezanne would have rendered the bulge of a mountain in a landscape.

Regardless of influences stemming from other art or his extensive travels, Hiroshi Yoshida brought a unique transcendence to his renderings of places. “Niagra Falls” stands as a masterpiece because of this quality. When first viewed the print could almost be a blue and white abstraction. A light puff of white in the center barely suggests mist. Aided by the title it becomes evident that this is a scene of foaming water headed over a precipice. As in “Grand Canyon” it is a perspective across the top of a huge natural phenomenon and subtly shows just two sides of a section of the falls with mist rising from the gap between them. Rather than a frontal view with spectacular expanses of cascading water, this is an uncommon close up of the impending descent. It is a metaphysical scene that echoes traditional Japanese nature philosophy. Although the void in the dark center has whirlpool-like intensity, the water impelled toward it is nearly calm with gracefully curving white foam. There are small motionless clouds in the sky that resemble the mist from the roaring falls. Enormous force and stillness are opposite aspects of the same reality.

Although his significant works were done before 1940, Hiroshi Yoshida continues to exert influence today. Masami Teraoka’s revival of woodblock prints with Pop Art comments on contemporary East-West trends is an obvious descendant, and the present day Taoist poet-sage Nanao Sakaki acknowledges Yoshida as an inspiration for seeing more deeply into the value of wilderness.

March, 2005

Reader Interactions